Pushing the reset button for South Sudan

Return Home

Return Home

In October 2021 at a meeting with officials from the Government of South Sudan (GoSS), we discussed the policies of the international community towards the new state of South Sudan, primarily shaped by the African Union Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan (AUCISS) and the reports of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS). The complaint was made that these and other international institutions had ignored and rejected the statements made by GoSS upon the causes of the conflicts within the brief history of this state and a completely erroneous narrative had been promulgated that prevented it from developing as a nation on its own terms.

South Sudan as a consequence of those narratives has found itself the subject of sanctions preventing it from acquiring military equipment necessary to protect itself from armed groups as well as restrictions that prevent it from proper commercial trading in its single most valuable resource – oil. Individuals who represent the state and challenge the approach of the international institutions have found themselves personally sanctioned for their resistance. In light of the findings in this report, the narratives are open to question.

This report publicly releases from South Sudan phone intercept communications and evidence obtained by an Investigation Commission formed by Presidential Decree1 in 2014 to conduct a criminal investigation against twelve suspects2 alleged to have taken part in an attempted coup on 15 December 2013. That attempted coup precipitated the conflict that followed from that date into 2014 and beyond. The sources we have reviewed establish the truth behind the violence that broke out in South Sudan, not only on 15 December 2013 but also a further attempted coup on 8 July 2016 that continued the conflict. The evidence supports President Salva Kiir’s statements at the time that these were attempted coups carried out by Dr Riek Machar and others, in which they planned to take control of South Sudan for themselves. In the intervening period between the coups, Machar continued his policy of conflict with the deliberate aim of seizing power.

The question must be posed as to why the international community, particularly UNMISS and AUCISS chose to disbelieve or disregard President Salva Kiir’s allegations of a coup attempt? The issuance of critical press releases condemning both parties, reveal a bias and misreading of what had taken place in South Sudan.

It resulted in international policy that was based upon a premise of distrust for the GoSS. The contextualisation by UNMISS of the conflict in December 2013 as being ethnically based resulted in a narrative that was quickly adopted and the rights of a state to protect its constitution and government side-lined. Too easily have claims of potential genocide been made to scare the international community by UN officials as the GoSS strives to work out political solutions.3 These claims are in fact destructive to the advancement of the nation and result in the imposition of international sanctions and restrictions. The approach of the UN Mission that they had to be “convinced” by the GoSS is baffling and does not excuse its lack of willingness to review and interpret materials later presented that contradicted a narrative it had too quickly issued. The failure to properly inquire and review materials provided by the GoSS in its defence in the form of the phone intercepts by AUCISS is equally baffling, particularly as it was prepared to make findings that rejected the defence. We have learnt from our experience of international cases that narratives too easily morph into policies that are only to be unravelled later.

The telephone intercepts reviewed by 9BR Chambers are authentic and reveal not only the planning of the attempted coups in 2013 and 2016, but also the discussion of the events as the conspirators put into action their plans, the impact of which have continued to sow division and separation throughout the country. The Investigation Commission conducted under the law of South Sudan heard direct evidence from those involved in the events of 2013 and corroborates the authenticity of the telephone intercepts, as indeed the intercepts cross-corroborate the evidence of the Investigation Commission. This report reveals how the international community got it wrong in South Sudan by ignoring what was said on its behalf in pursuit of a preconceived agenda for western led policies and solutions.

The findings in this report suggest that it is now time for the international community to push the reset button in respect of how the events of the past ten years have been perceived and in so doing, how the future governance of South Sudan should proceed on terms for reconciliation, peace and justice that are workable within its unique history and experience.

Steven Kay QC

9BR Chambers

London

March 2022

Since the creation of South Sudan in 2011, international institutions have ignored or rejected statements made by President Kiir and the Government of South Sudan on the causes of the two main conflicts in 2013 and 2016. This stance has led to the promulgation of an erroneous narrative that has prevented the world’s youngest nation from developing on its own terms.

In this report, 9BR Chambers publicly releases for the first time, information from phone intercept communications, reports, witness statements and other sources to establish the truth behind the violence which broke out in the attempted coup on 15 December 2013 and the subsequent coup attempt on 8 July 2016. The sources reviewed prove the truth of President Kiir’s contemporaneous statements, namely that both attempted coups were carried out by Dr Riek Machar and others with the aim of taking control of South Sudan for themselves.

This report contradicts the narratives issued by the United Nations Mission in South Sudan as to the nature of the conflict as well as the report of the African Union Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan that investigated the first attempted coup of December 2013 and found no evidence to support the assertions of the President of South Sudan and other leading officials.

Chapter 1 sets out the evidence as to how Riek Machar planned the attempted coup of 15 December 2013 by both military and political means. Taban Deng Gai led the military efforts in coordinating troops and weapons with Brigadier General Peter Lim Bol Badeng Commander of Tiger Brigade 1 and other officers in the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). The telephone intercepts reveal how the conspirators put into action their plans. This evidence corroborates the evidence produced in the Investigation Commission formed by Presidential Decree in 2014 conducted under the law of South Sudan.

President Kiir’s explanation of 16 December 2013 was reported widely as an ‘alleged coup’ but framed as violence along ethnic and political lines. This misinterpretation of events led to a hastily introduced prescribed formula for peace-building and lengthy international intervention ever since; based upon an erroneous narrative, namely that the violence was political and ethnically targeted.

Chapter 2 analyses the response of the international community to the attempted coup in December 2013. Crucially, the United Nations, African Union, USA, and EU did not describe the events of 15 December 2013 as an attempted coup. The preferred international response was of a political ‘crisis’ that escalated to violence carried out by the military and various armed groups. Ethnicity and political factionalism were named as the overriding causes. This narrative enabled prescribed responses to fit a humanitarian agenda.

The peace agreements thereafter have been underpinned by a need to address ethnic differences, largely informed by external perceptions of these events. These agreements have largely failed as ethnicity has been exploited by Riek Machar to undermine President Kiir and the Government of South Sudan. The more conflict the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army-in-Opposition (SPLM/A-IO) can cause, the more they can increase international pressure on President Kiir and the GoSS. Such international pressure has perceptibly prevented the development of the country and kept it locked in a prism of international control.

Chapter 3 examines the interim events between the two attempted coups which illustrate a continued effort by the SPLM/A-IO under the leadership of Riek Machar to undermine and protract peace negotiations, exploit factional divisions and ultimately, destabilise the GoSS. All these activities frustrated the development of the country and resulted in the diminution of its international status.

The Government’s efforts to restore peace and stability in South Sudan following the attempted coup in December 2013 were immediately swept aside as the opposition took advantage of its position within the protracted peace negotiations throughout 2014 to 2016. Significant efforts were made by President Kiir to ensure peace with repeated attempts to reach out to the opposition and notable concessions.

In contrast, the opposition made no attempt to return the goodwill or to progress efforts to stabilise South Sudan. At each stage of the peace negotiations, the primary goal of the opposition led by Riek Machar was to undermine the Government and to overthrow President Kiir. These efforts were concretely put in motion with military assistance from foreign entities and continuous efforts to delay, stall and compromise peace efforts.

Ultimately, Riek Machar’s signature of ARCSS in August 2015 was not a genuine attempt to power share as evidenced by his own words a month before when on 8 July 2015 he declared that should President Kiir not resign then the “citizens have every right to rise up and overthrow his regime”.

This imbalance of efforts was overlooked by the international community and the opposition gained significant traction as Machar was provided with extensive powers as First Vice-President in 2016. Yet even then, Machar continued to plot to overthrow President Kiir in furtherance of his own grand ambitions to be President of the Republic of South Sudan. This culminated in the attempted coup on 8 July 2016.

Chapter 4 examines the attempted coup of 8 July 2016. Following his return to Juba in April 2016, Riek Machar launched a charm offensive promoting peace, unity and solidarity with the government. On 8 May 2016, he called for “forgiveness and reconciliation in South Sudan”. On 22 May 2016, Machar attended prayers at a predominantly ethnic Dinka church on Sunday, telling the congregation “that peace and reconciliation will enable national healing and ensure stability.”

However, the evidence from telephone intercepted communications from the same period reveal that Riek Machar as First Vice President of the Transitional Government of National Unity (TGoNU) plotted a coup to seize power on 8 July 2016. Whilst he was presenting a unified front to the international community, in the background he was at the same time preparing forces of the SPLM/A-IO to carry out the coup and using support from a foreign government, the Republic of the Sudan, to provide his forces with the necessary arms and ammunition. When the coup failed in its initial stages during his meeting with President Kiir and Second Vice President James Wanni Igga in the President’s office, Riek Machar never resumed the reconciliation talks that had been taking place between the leaders of the TGoNU. Instead, he continued the conflict that caused great loss of life including the deaths of civilians, knowing from his experience over many years of conflicts in South Sudan and Sudan that such killings were inevitable.

The institutions of the United Nations were bound by the narrative they had followed from the time of the first attempted coup in December 2013, to continue with the same humanitarian agenda they had invoked against the GoSS. This narrative remained locked in the prism that the conflicts were ethnically driven, and responsibility was shared between the protagonists. The institutions of the United Nations did not recognise that the coup attempts were the result of the pursuit of an ambition that stoked and utilised ethnic divisions. It also failed to recognise adequately the rights of a sovereign state to control its territory and prevent the unlawful and violent attempts to usurp the lawful structures of power and government.

The findings in this report suggest that it is now time for the international community to push the reset button in respect of how the events of the past ten years have been perceived and in so doing, how the future governance of South Sudan should proceed in respect of reconciliation, peace and justice in ways which are workable within its unique history and experience.

Background of Escalating Political Tensions Leading to First Attempted Coup

South Sudan became an independent state in 2011, having been forged out of conflict, with all the component elements of conflict remaining within its borders. It did not take long before tensions between Vice-President Riek Machar and President Kiir rose, driven largely by Riek Machar’s desire to become the next President of South Sudan and his vocal criticism of President Kiir. These tensions were heightened by the scheduling of national elections due to be held on 9 July 2015. Suggestions that President Kiir may step down after the 2015 elections led to others positioning themselves as next in line.4

By March 2013, Riek Machar had disclosed his ambition to replace President Kiir as Chairman of the SPLM and ultimately to become President of the nation.5 Throughout 2013, Riek Machar was planning and organising his forces in the regions in preparation for rebellion. This mobilisation is why within 48 hours of the outbreak of fighting on 15 December 2013, Riek Machar was coordinating and mobilising troops from Unity State in a bid to overthrow the Government of South Sudan.6

The stripping of ‘all duly delegated powers’ of Riek Machar under the 2011 Transitional Constitution on 15 April 2013 by Presidential decree7 did not deter him. Indeed, on 4 July 2013, he declared in an interview that he was not prepared to wait to take power in 2015 and was ready “for a change now.”8 He later accused President Kiir’s actions as a “violation” of the party constitution and having no constitutional power to dissolve party structures until the National Liberation Council meeting was held.9 The Constitution adopted on 2011 gives President Kiir broad authority to dismiss senior government officials.10

In a major cabinet reshuffle on 23 July 2013, announced by presidential decree on State television, President Kiir dismissed his entire cabinet (with the exception of four ministers) along with Vice-President Riek Machar. President Kiir had initially wanted a cabinet of eighteen cabinet ministers with international donors pressing for a leaner and more effective set-up.11 The reshuffle was to restructure the government and aimed to avoid ethnic violence.

Provoked by his dismissal, Riek Machar announced again that he would challenge President Kiir for the Presidency.12 Machar’s removal from office had the effect of precipitating the mobilisation of his supporters against President Kiir thus creating political division which would ultimately divide the nation.

In the months leading up to December 2013, the National Security Agency (NSS) and law enforcement agencies were alerted to the continuing dangers of division within the SPLM and the potential serious consequences for the security of the nation. Consequently, attempts were made by the Minister of the Interior, Director General of National Security and the Director General of External Security along with the Director of Military Intelligence, to engage in dialogue with Riek Machar and his supporters, urging them to reach a political compromise so as to avoid plunging the country into serious political and social crisis.

Riek Machar held a press conference on 6 December 2013 and announced that he planned to conduct a public rally to garner support for his campaign against the government.13 This press conference heightened the internal party crises and provoked fears among citizens.14 The rally was later cancelled as the government scheduled the voting session for the new National Liberation Council of the SPLM on the same day. Machar’s intention however, to become the next President of South Sudan was clear.

On 8 December 2013, the Vice President, James Wani Igga, responded publicly in a statement denouncing the disaffected SPLM leadership as irresponsible and undisciplined. The Vice-President cautioned the group against inciting the army and creating instability in the country.15

Tensions were running high following the press conference on 6 December as the SPLM National Liberation Council (NLC) meeting scheduled for 14 and 15 December 2013 approached. This meeting, repeatedly postponed, was aimed at discussing and approving key SPLM documents, namely its manifesto, constitution, code of conduct and regulations.

On 14 December, the first day of the meeting, contentious issues arose including: (i) the voting method (whether it should be by secret ballot or a show of hands); (ii) the proposed nomination by the President of 5% of the delegates that would eventually elect the party officials, including the party’s Presidential candidate for the 2015 elections; and (iii) the election of the party’s Secretary General.

On 15 December, the party proceeded to adopt the constitution, manifesto and code of conduct. Although Riek Machar and a large contingent of his supporters attended the first day, their numbers dwindled by 15 December16 when it became apparent that Riek Machar would not win the Chairmanship of the party and the NLC was boycotted.

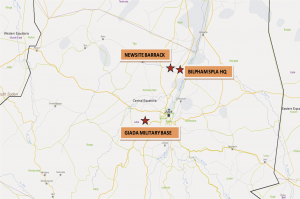

At around 9pm on 15 December 2013, fighting broke out at Al Giada barracks,17 the former Government Military Headquarters in Juba,18 spreading thereafter to New Site19 and nearby Bilpam,20 the Headquarters of the SPLA.

B. Telephone Intercept Evidence

(i) Preparing for a Coup d’Etat

29 October 2013: Major General Peter Gadet Yak, Commander of the SPLA Infantry Division 8 in Jonglei State21 was assigned by Riek Machar to mobilize the White Army in Lou Nuer areas and connect them with the insurgency group based in the Pibor area known as the Cobra Movement under the command of David Yau Yau.22 Gadet was seeking logistical support “for change to happen in the Government”.23

29 October 2013: Peter Gadet mobilised support and weapons directly from Khartoum under Khalid Butrus24 – a key liaison officer for weapons supply from the Sudan Government in Khartoum – and coordinated with David Yau Yau and Major General James Kong Kong (1st in Command under David Yau Yau, Cobra Movement). Gadet told Butrus: “that the situation in the country is very bad and people are also very desperate.” He added that: “everything will be ok if they can get the supply from Khartoum.”25

30 October 2013: Peter Gadet spoke with Major General James Kong Kong seeking assistance for the White Army youth to be sent to Pibor areas for the assembly with the forces of the Cobra Movement. James Kong Kong agreed to send enough forces to Bor for a joint operation with Gadet in Pariak and the White Army Youth. Gadet inquired about weapons for the White Army Youth. He advised that they should keep communications open using Thuraya (Satellite) only.26

30 October 2013: Peter Gadet revealed he needed help from David Yau Yau for weapons and ammunition. He informed James Kong Kong that: “their forces are ready”.27 Gadet added that they are planning for a new idea and he asked if Kong Kong is ready with the forces so he can be directed to the meeting place to get support: “Their idea is to organize about 12,000 troops so as to attack and capture Bor up to Pariak”. Gadet advised that he could help James Kong Kongs’ forces with the route to Bor.28

(ii) Political Build-Up – December 2013

Riek Machar’s intention was to make a bid for the Presidency of the SPLM at the upcoming NLC meeting. Telephone intercepts show a series of calls were made to establish how much support he had.29 When it was apparent that Riek Machar would not win the Presidency during the NLC meeting of 14 December, he and his team boycotted the following day’s meeting.30 The intercepts show how events were brought forward following suspicions that the coup plot had been discovered.31

On 6 December 2013, at 09.12 Riek Machar’s press secretary Steve Lam called George Sebit, Security Advisor in the Office of Governor of Central Equatoria State, to tell him to come to Riek Machar’s press conference that day with youths from Equatoria. Lam passed details to Sebit of a young man in Nairobi who would work with mobilizing the youth.32 Lam emphasised the importance of Sebit’s teams’ presence at the press conference so they could later brief their communities on the importance of good leadership.

6 December 2013: At 11.0633 MaMach a youth leader of the Nuer from Nasir in Upper Nile State, called Agok Makur to inform him of Riek Machar’s press conference. MaMach stated that he was in the village mobilising the White Army and that if there was a need for support from the grass roots they would facilitate this.

(iii) National Liberation Council Meeting

13 December 2013: At 08.21 MaMach, called Pagan Amum to discuss the SPLM conference and informed him that there are youths in Juba so Pagan need not be worried about the government.34

14 December 2013: At 07.3935

Taban Deng Gai discusses the NLC meetings with Brig. Gen. Peter Lim Bol Badeng, Commander of Tiger Brigade 1:

TDG: Have you been given your orders yet?

PL: We have not been given orders yet.

14 December 2013: At 8.3036 Taban Deng Gai spoke with Captain Tai Matien officer in the National Security Service:

TM: The planned meeting was not postponed you should not make the mistake of going to the meeting. You will be defeated at the meeting.

TDG: They should be prepared to fight if they are dismissed by those people and we see who will be chased.

14 December 2013: At 08.4437 Taban Deng Gai speaks with Riek Machar about the NLC meeting and alliances:

RM: Have you spoken to the forces?

TDG: Yes I have, they have not yet received their orders.

TDG: You have to be careful.

14 December 2013: At 09.3638 Pagan Amum received a call from Theji Dedut concerning the SPLM conference on 15 and 16 December. Pagan Amum said they could not go to the meeting unless they had their own force, and advised they needed to meet and not talk on the phone, they will meet somewhere to decide to “fight the dictator”.

14 December 2013: At 22.4839 Taban Deng Gai speaks with Ezekiel Lual Gatkuoth, former South Sudan Ambassador to the USA, who informed Taban that there had been an “infiltration” in their forces that had gone to the President concerned about the money. Taban says he suspects certain individuals who it may be. Ezekiel offered to bring three officers tomorrow to see Taban.

14 December 2013: At 21.4840 Taban speaks to Chuol regarding phones. He confirms the phones have arrived and are configured. Taban told him to make sure they were all programmed and well-charged ready for use. He tells Chuol that once they are ready to bring them to his home anytime.

(iv) Final Preparations for the Coup – 15 December 2013

Taban Deng Gai had no military command but during the day of 15 December 2013, he made a series of telephone calls to serving SPLA officers to carry out the plan to stage a military coup and seize power for Riek Machar. The plan was put into operation as a result of the failure by Riek Machar to gain sufficient support for his bid for the Presidency of the SPLM at the NLC the previous day. The recordings and transcripts of intercepted phone calls from the phone of Taban Deng Gai reveal the preparations and execution of the planned coup. Some of these are set out below:

15 December 2013: At 12.5541 Taban Deng Gai calls Lt. Col. Stephen Gueh42 and inquires over the forces and their readiness – “the force will be ready for tomorrow or today?” Gueh answered that it would depend on Taban Deng Gai and Gwardit’s [Riek Machar] position.

15 December 2013: At 13.0243 Taban Deng Gai calls Lt. Col. Peter Lok Tang:44

TDG: What will you do in the Parade?

LT: What is your solution?

TDG: I met your Commander he will brief you on what we discussed.

TDG: There are things we have not yet decided.

TDG: You go to Brigadier Lim he will update you.

TDG: Let them not surprise you.

LT: This is my job.

15 December 2013: At 14.4045 General Oyai calls Taban Deng Gai to say they should meet at Taban’s house and that General Majak de Agot46 was already there.

15 December 2013: At 15.0547 Taban Deng Gai calls an officer of the Tiger Division and asks for the contact of Brigadier General Kuol Chuol.48

TDG: Do you know his parade?

Officer: We have 50 arms.

Officer: We have many young people.

15 December 2013: At 15.4749 Taban Deng Gai calls Makur Kulang, former Commissioner of Yirol West to report they will boycott the NLC meeting.

15 December 2013: At 17.1950 Taban Deng Gai handed his mobile phone to General Oyai Deng Ajak51 former Chief of Staff of SPLA, who spoke with an officer. In the conversation, General Oyai believed that the additional 200 soldiers were not professional soldiers and therefore would not put up much resistance to better-trained militia.

15 December 2013: At 19.1852 Taban Deng Gai speaks with Brig. Gen. Peter Lim Bol Badeng of the Tiger Brigade 1 who informs him of a plan to arrest 1st Lt. Riek Manguan53 for bringing money to pay soldiers allegedly “wrapped in a bed sheet and came in a car”. Brig. Gen. Peter Lim Bol Badeng suggested they should start their programme tonight instead of tomorrow. This was the communication that put into action the plan for the coup that was originally scheduled for the 16 December.

TDG: Do you think we can the resist the situation tonight?

Lim: We can resist but our concern is the issue of guns and artillery. The armoured vehicles are going to affect us.

TDG: If the armoured cars are taken away from you in the daytime what can you do?

Lim: The problem is tomorrow they have ordered his arrest, we are concerned if we resist the arrest, the number is bigger. We cannot do anything. If we are the one planning it we can take the 21 cars. If they are planning we will divide the armoured cars.

15 December 2013: At 19.4854 Taban Deng Gai speaks with Captain Bedong Yuai Majok from a Commando unit based in Kapoeta regarding the situation and checking they are ready:

TDG: Do you follow the people of Brigadier Lim?

BYM: Yes we are following up with their people”

TDG: Are your people ready?

BYM: Yes.

TDG: Okay I will call you later but you yourself need to be ready.

15 December 2013: At 20.2455 Taban Deng Gai talks again to Brig. Gen. Peter Lim Bol Badeng and they discuss the arming of their forces.

PLB: A Major in 1st Battalion of Tigers issued an order for 10 guns to be removed from the store. Those guns were given to his [President’s] people for duty. I ordered them to take them back as they were for ordinary duty.

TDG: Today you will take your guns.

PLB: Yes we will take our guns. The two gentlemen will now go to the garrison.

TDG: Yes let them go.

TDG: Take all those who are armed to the house of Dr. Riek.

PLB: They have noticed something.

15 December 2013: At 20.4156 Taban Deng Gai speaks with an officer on duty at the John Garang Mausoleum to report on the number and ethnicity of forces:

Officer: My force is 57 of which 24 Dinka, 33 from Equatoria.

15 December 2013: At 21.2257 Taban Deng Gai called General Oyai to tell him that things would be bad tonight and that Riek Machar: had already authorized that the soldiers should break the stores and take their guns.

(v) Telephone Intercepts Ordering the Coup – 15 December 2013

15 December 2013: At 21.3658 Taban Deng Gai spoke with Lt. Col. Stephen Gueh and we hear the start of the attempted coup:

SG We have reached the garrison. How are you doing now?

TDG: We are doing okay. We have given you the orders.

SG: Are you waiting for Lim?

TDG: You continue with your work.

SG: Son of Machar [Riek Machar] is leaving now and going to a safe place.

TDG: I am told that one of our relatives has run away with the keys.

SG: They are progressing well with their work and shall start within time.

15 December 2013: At 21.5059 Taban Deng Gai spoke with another officer who asks whether a senior person has been arrested. Taban informs him no one has been arrested but a few officers within the Tiger Division will be arrested tomorrow.

15 December 2013: At 22.0260 Taban Deng Gai called Lt. Col. Peter Lok Tang who informed him they were ready and in their positions.

TDG How are you guys?

PL: We are doing well. We are waiting for Brigadier Lim he is outside.

TDG: Let them not attack you first.

PL: This will never happen.

TDG: If Lim delays you should not wait for him, you start your guns. If Lim is delaying get your guns.

PL: I want them to come in with us to the garrison.

15 December 2013: At 22.2961 Taban Deng Gai called General Oyai to inform him firing had started. General Oyai says he is in the house of General Deng Alor and expresses surprise at the speed of matters. Taban told him to stop his meetings with Deng Alor as nothing will come of it. General Oyai agrees to leave the house immediately.

15 December 2013: At 22.3762 Riek Machar calls Taban Deng Gai to inform him that the fighting has started. Taban asks if he has left his house yet. Machar tells Taban he has not and he thinks there is no point in leaving yet. Taban tells him to stop thinking like that and he should just take the small car and leave the house immediately. Riek Machar agreed that he will see what he can do.

15 December 2013: At 22.4363 Taban Deng Gai called Brig. Gen. Peter Lim Bol Badeng who informed him about the violence at Giada.

PL: We have started fighting.

TDG: Is it true they did not surprise you?

PL: We surprise each other.

TDG: Have you started fighting?

PL: We chased them out from the Headquarters.

TDG: Your people who are outside let them join you.

TDG: You have chased them from their positions do you think they have taken guns with them?

PL: We will organise a parade.

TDG: If you capture people don’t kill them.

15 December 2013: At 23.0264 Taban Deng Gai receives a call from a Captain in the Presidential Guard.

Capt: All the cars and tanks of the Tiger have been captured.

TDG: Let them set up the guns on the cars. Is there anything coming from the artillery unit?

Capt: Nothing coming from there.

TDG: Give them reinforcements.

Capt: Yes.

15 December 2013: At 23.1865 Taban Deng Gai speaks with Lt Col Lok Tang.

TDG: How are you going?

LT: I am in the barracks.

TDG: That’s good. Did Those of Brigadier Lim come to you?

LT: Yes they are on the other side of the barracks.

TDG: Who is there controlling the tanks?

LT: I do not know but only maybe Brigadier Lim may know that.

TDG: Have you captured their store?

LT: Yes we are now breaking the store.

TDG: You have not yet broken it?

LT: It is very difficult as there are big locks and we do not have a hammer.

TDG: Everyone has got a gun right?

LT: Yes all of them have got.

TDG: You open the route for others to come to your enforcement.

LT: Yes we have prepared everything and we also briefed ourselves that we cannot shoot anyone randomly.

TDG: You don’t kill somebody if he is not fighting you because this is a government fight.

You just break the store quickly.

15 December 2013: At 23.1966 Taban Deng Gai speaks with Lt. Col. Stephen Gueh, firing can be heard in the background and Taban is coordinating weapons and troops:

TDG: How are you going in the barracks?

SG: We are doing OK. We have captured everything as I told you before.

TDG: What about the support weapons have you mounted the vehicles? This is what we asked?

SG: We have done everything. We have captured all the cars.

TDG: Have you mounted the cars?

SG: We will mount them.

TDG: You mount them up. Wrap them with the ropes to mount them.

15 December 2013: At 23.3267 Taban Deng Gai speaks with Lt. Col. Stephen Gueh again.

SG: Where is the big man?

TDG: He left behind me to his farm where you grafted the land last time. He is safe.

SG: What about Madam and Majak?

TDG: They have no problem and we shall get them tomorrow.

15 December 2013: At 23.5068 Taban Deng Gai informs General Oyai their forces captured the headquarters at Al Giada.

TDG: I have just heard there is enforcement coming to the field. I have heard your house is surrounded.

GO: I left my house I went to the house of General Hoth. I will go back to my house now.

TDG: How will you go there?

GO: There is no problem I will go.

TDG: Please call me when you reach home so I can give you the report.

15 December 2013: At 23.5369 Taban Deng Gai updates General Oyai.

TDG: It seems they have captured the area.

GO: OK.

TDG: It seems they have captured the tanks, but I will confirm. I do not know the force of the other side and where they will come from. There are reports that they are coming from Luri. I do not know whether this is true. They have captured all of the vehicles. I told them they should mount the supporting weapons on the vehicles. The soldiers are complaining there is no welding, I told them to use ropes. I am not getting Brigadier Lim now, I will call him later. He told me he will call me but he has not yet. Have you reached home?

GO: I have.

TDG: Is it true the house is surrounded?

GO: Yes.

TDG: Are you going to sleep there?

GO: Going out will be difficult now.

TDG: You should relay the reports to me.

16 December 2013: At 00:4670 Taban Deng Gai speaks with Brig. Gen. Peter Lim Bol Badeng:

TDG: Where are you? Have you reached?

PL: You must leave the house and join me come like you are going to…

TDG: Where are those of Lok Tang?

PL: Some forces of Battalion 1 went to…….some forces still at the barracks.

TDG: How come some are still at the barracks?

PL: Those of Lotan are…but the others are in the barracks.

TDG: If they are still in the barracks why don’t they get reinforcements?

PL: I have just heard the tanks have been given instructions to move.

TDG: Okay.

16 December 2013: At 00.5271 Taban Deng Gai speaks to Brig. Gen. Peter Lim Bol Badeng:

TDG: Where are you? Have you reached Mangateen?

PL: Yes.

TDG: Do you know the Big Man has left his house?

PL: They refused to tell me the location.

TDG: Have you contacted those guys again?

PL: Yes we are talking on the phone right now.

TDG: Is that Lok Tang talking to you?

PL: No his phone went off.

TDG: Where is the other Lieutenant?

PL: I am trying his number now.

TDG Who is that telling you they are still in the barracks?

PL: I got that from …..

16 December 2013: At 00:5972 Taban Deng Gai speaks to Lt. Col. Stephen Gueh

SG: We are the ones shooting.

TDG: Did you manage to break the stores?

SG: We broke the stores and took out the guns.

TDG: You opened the roads for the people to come?

SG: All the civilians came to us and received the guns.

TDG: Congratulations.

SG: The civilians are not going back they are fearing of the tanks.

TDG: They will come back tomorrow.

TDG: Ok you control that side.

SG: We are not going back it will never happen that we can be defeated by Dinka.

16 December 2013: At 01:4573 Taban speaks with Brig. Gen. Peter Lim Bol Badeng:

TDG: Are you still OK?

PL: Yes.

TDG: Have you talked to your forces?

PL: Those guys are still in the barracks all of them. They have control of the areas.

DG: Are there civilians or youth that have joined you?

PL: All the youth have come, they grabbed the guns and went back.

TDG: Is this true?

PL: Yes they run away and I think they will come back tomorrow.

TDG: That is not good. Have they captured Bilpam?

PL: Not yet but they are around the periphery.

TDG: Those guys are still in the barracks, I told them if you have a problem you come to this side.

TDG: How did those people get to you?

PL: One of the tanks went in and nobody took care of that.

TDG: Have you captured anti-tanks?

PL: No we do not have anti tanks.

TD: This is going to be a problem tomorrow.

16 December 2013: At 03.0174 Taban Deng Gai receives a call from Ambassador Ezekiel Lual Gatkuoth.

EZ: How are you going?

TDG: Are you still in the hotel or have you gone somewhere?

EZ: I am still in the same place.

TDG: If you have something you go to your Embassy.

EZ: They have control of the National Security including the other.

TDG: No we do not have control of National Security they have control of the barracks. Bilpam is still not controlled.

EZ: He ran away (President).

TDG: No he did not run he is still around.

EZ: He is still around?

TDG: Who told you NS has been captured?

EZ: It is the guys in the theatre who informed me.

TDG: National Security went for attack but they repelled them. Our guys who are the NS did not do any work.

EZ: OK You bring reinforcements? I have already informed Washington you bring reinforcements I told them what provoked people was the speech, also the arrests that is what caused the thing.

16 December 2013: At 03.4375 Taban Deng Gai speaks with an officer in the Tiger division who confirms they are readying an attack on the National Security HQ in the morning.

TDG: Are you in the same place?

Officer: Yes. We are in the Presidential Guard.

TDG: Where?

Officer: In Tigers.

Officer: We are the people who fought with the Dinka.

TDG: You are in the others.

TDG: How did you do with the security?

Officer: We have made a deployment we will see tomorrow.

TDG: Did you get tanks?

Officer: No the tanks are chasing out.

TDG: I was told you got 2 or 3 tanks.

Officer: No. We broke the armoury stores but we have not yet got the anti-tanks. We are looking for the ammunition store.

TDG: Are you more? Have you been joined by the youth?

Officer: They have joined us, they are making defence our side.

16 December 2013: At 05.1376 Taban Deng Gai calls Lt. Col. Malual.

TDG: Where are you?

Malual: We are in the barracks.

TDG: They have not yet attacked you?

Malual: No the only attack that happened was at 2 o clock with the tanks.

TDG: The Battalion is still with you?

Malual: They are on the other side of the barracks and we are defeating them.

TDG: Did the youth join you?

Malual: Yes they came to us we give them the guns.

TDG: Where are they now?

Malual: They say they were in the fighting then ran away because of the firepower of the tank.

TDG: Did you load the artillery?

Malual: We loaded the artillery including 12, the problem was the drivers took the keys of the cars.

(vi) Weapons supply from Sudan and further planning – January 2014

Transcripts from January 2014 show Taban Deng Gai and Riek Machar continuing to arm and mobilise militia in their attempts to overthrow the government of President Kiir. Importantly, these intercepts evidence coordination with contacts in Sudan to obtain military supplies.77 Intercepts for 16 January 201478 show conversations between Maj. Gen. James Koang Chuol and Dr Lony in Khartoum coordinating the weapons supply with Maj. Gen. Michael Chiengjiek.79

On 19 January 2014, Taban Deng Gai discusses with Lt. Col. Parjiek Toang Liak about “working hard to destroy Kiir’s government in Juba” and that they will now establish a base in Upper Nile to crash the government. Taban Deng Gai reiterates the support of the Sudan Armed Forces and that Parjiek should open the route for military support.80

Maj. Gen. Michael Chiengjiek called Brig. Gen. John Mabieh Ger on 19 January 2014, to discuss coordinating and receiving weapons from Upper Nile and in particular Kuek on the border with Sudan. During this call, Mabieh confirms to Chiengjiek that the forces in Akobo received their weapons supply.81

Taban Deng Gai confirms with Col. James Kurt Puot on 19 January 2014 that the “people in Khartoum” will be sending military supplies by road, not air to avoid the Americans intercepting. He suggests Brig. Gen. Makal Kuol should receive and organise the transportation urgently as he will be coming with the trucks from Heglig the following morning.82

A further call on 19 January between Taban Deng Gai and Burchot, an officer from Leer County, also reveals the supply of weapons from the Sudan Armed Forces via road. Taban Deng Gai informs them that they “must fight to return to the north of Bentiu so as to link up with trucks carrying the cargo which is now escorted by Brig. Gen. Michael Makal Kuol”.83

On 20 January 2014, Taban Deng Gai confirms good relations with Khartoum to Lt. Col. Parjiek Toang Liak and assigns a “smart MI officer to handle the coordination”. Taban Deng Gai confirms that Michael Parjiek is known in Khartoum and to inform the Sudanese Armed Forces that directives from Riek Machar’s headquarters for military equipment are to be supplied through Kuek.84

On 20 January 2014, Riek Machar is also recorded having conversations with Sergeant Matek based in the Kuek border post about permitting military vehicles through. A later call between the two reveals the police refusing crossing and a shoot-out ensues. Riek Machar states he will coordinate with Khartoum to “complete the coordination”.85

C. The South Sudan Investigation Commission

In January 2014, an Investigation Commission (Commission) was formed by Presidential Decree86 pursuant to Ministerial Order No 2/2013 from the Minister of Justice to conduct a criminal investigation against twelve named suspects87 alleged to have taken part in the attempted coup on 15th December 2013. Five individuals in respect of whom arrest warrants were issued could not be located. These were Riek Machar; Alfred Ladu Gore; John Malual Biel; Taban Deng Gai and Brigadier General Peter Lim Bol Badeng.

“On Sunday 15/12/2013 the suspects above have attempted to overthrow the government by force using dangerous weapons and the incident resulted in the death of 600 soldiers including civilians approximately, destruction of public properties and private, created desertion amidst organized forces and army, breach of security and peace in Juba and the displacement of innocent civilians.”88

Evidence obtained by the Commission provides insight into how the coup attempt in 2013 was planned, including information about the role of Brigadier Peter Lim Bol Badeng,89 Colonel John Malual Biel90 (the personal bodyguard of Riek Machar), Lt Colonel Ruei Nyochom91 and Riek Machar himself. The reliability of the evidence is corroborated by the telephone intercept records produced in the first section of this chapter. A summary of the evidence within the Investigation Commission’s Case Diary, from witnesses who testified is set out below:92

Major General Saaid Chawul Lom, a former Inspector General of Police testified that he went to the Directorate of Operations in the early hours of the morning. There he found all police forces assembled and the Minister of the Interior, Aluei Ayian briefing them that a “group of political leaders under Riek Machar, Taban Deng and others had attempted to take power by force using military personnel and other organised forces which resulted in the loss of lives of innocent persons and soldiers that night.”93 It was after this meeting that a committee of three senior officers was formed, (General Lom, Major General Paulino Dodor and Major General James Bol), tasked with initiating a criminal case and carrying out the arrest of those suspected of involvement in the coup attempt.

Major General Paulino Dodor, one of the three senior police officers tasked to initiate a criminal case explained to the Commission that money was distributed to soldiers who were attempting to overthrow the government.94 He stated that “we have soldiers who belong to protection guard of Tiger, they said the money was brought from Commercial Bank, but I did not know the total.”95

Major General James Bol Nyok stated that Major General Marial Chanuong briefed him and his colleagues on the attempted coup and that Riek Machar and others were said to be behind the incident.

Private Kong Kutei Kai, from the Tiger Unit stated that he and other soldiers were attacked heavily by Nuer Tiger soldiers under the command of Brigadier Peter Lim. The same attackers, including civilians, moved to the armoury, broke in and took guns and ammunition. They came with drivers and five new Land Cruisers, which had been parked at the Tiger Headquarters. Private Kai stated that he believed Brigadier Peter Lim was behind the attempted coup and that Lim knew the politicians behind it.

Private Arop Chan Akech, from the Tiger Division heard information that Brigadier Peter Lim was distributing money to Nuer soldiers, brought by a car which stopped at the residence where Nuer stayed, a short distance from the Tiger HQ.

Sergeant Martin Abouk Baak, from the Tiger Division stated that on 15 December 2013, he had been on duty at the military hospital near the Tiger HQ and that he had been surprised to hear shooting nearby. At around 11pm, the fighting subsided and he went with others to the Tiger HQ and was informed that the attackers had withdrawn in the direction of residences in South Tiger and Jebel Market. In the early hours of 16 December, the attackers assaulted again, advanced to the armoury store, broke in and took rifles and ammunition. By this stage, Baak had been wounded and was evacuated to the military hospital. He had also heard that money was brought by a car into a Nuer residential area and that Brigadier Peter Lim was distributing it secretly to Nuer fighters, something he did not personally see.

Major General Marial Chaunoug, the Tiger Division Commander heard shooting at Al-Giada on 15 December 2013 at around 10.17pm. Moving to the scene, he called his officer Bol and asked him what was happening. He was told that soldiers were rebelling. Chaunoug immediately contacted Chief of Staff James Hoth by phone to inform him of the situation. On arrival at Al Giada, Chaunoug was shot at and his bodyguard responded with return fire. Officer Bol had informed him that the rebelling soldiers were from Tiger Brigade Units 1 and 2. There were also many soldiers present who did not belong to the Tigers and civilians. He recounts that the rebel soldiers broke into the armoury store and took the rifles.

When Major Akuol Reech, Deputy Commander arrived and asked what was happening, officer Lt. Col. John Malual Biel, the second Commander of the Brigade (and the personal bodyguard of Riek Machar) shot him dead. Fighting continued up to 2am on 16 December and Chaunoug brought tanks that forced the rebels to disperse. The rebel forces consisted of 162 officers of different ranks and 2,000 other officers, all of them belonging to the Tigers under the command of Brig. Peter Lim. He told the Commission that it was Lt. Colonel John Malual Biel who released the first bullet in the fighting at Al-Giada. He also stated that when Riek Machar asked Peter Lim what was happening by phone, Lim responded by telling him, “we have started.” Chaunoug also gave evidence that Lt Colonel Ruei Nyochom was distributing money but when he asked him about it, Nyochom told him that he was distributing the salaries of soldiers on mission.

Brigadier Inyasio Agang Deng told the Commission that he believed the fighting to be organised because “they targeted the armoury store and Bilpam” but he thought “there was no central command and control.”

Brigadier Atem Benjamin Bol, an SPLA member in the General Administration in Bilpam explained that on Monday morning once the report had spread that Riek Machar was behind the attempted coup, most of the Nuer soldiers did not report for duty.

In addition to SPLA members and police officers, the Commission also heard evidence from intelligence agency officials on the lead up and immediate aftermath of the attempted coup. These individuals gave evidence about the roles of Riek Machar, Taban Deng Gai, Colonel Gaton, Major General Marial Oyai Deng and Samuel Gatkoi.

Major General Mac Paul Kuol, the Director of Military Intelligence stated that on 8 December 20131 he met with Taban Deng at his house and explained to him the danger of popular uprising and military confrontation. Taban Deng96 appeared angered by this conversation. Kuol explained that on 6 December, Riek Machar and Rebecca Nyadeng held a press conference airing their grievances against President Kiir.

11 December 2013, Kuol explained rumours were circulating that Major General Marial Chanuong tried to disarm the Nuer soldiers of the Tiger Brigades. Kuol contacted Marial but he denied the allegation stating that there was instruction from the command to put rifles in the armoury, except those authorised or on duties.

12 December, he received reports that Brigadier Peter Lim had brought money in a car covered by bed sheets and was distributing it to Nuer soldiers and civilians in the rate of 2,000 SSP per person. Kuol explained that Major General Marial had been informed and had investigated the officer who had denied the allegation stating that what he was distributing were the salaries entrusted to him. Kuol also states that he informed the President about the abnormal situation emerging “at Tiger” but no precautionary measures were taken at that stage.97

Major General Akol Koor Kuc,98 The Director General of the Internal Security Bureau, gave evidence that he had met with Riek Machar on 12th December 2013 and explained to him the highly tense political situation and serious consequences that could result depending on actions taken. Seven days later, Riek Machar replied stating “Dhaal”, a word in Nuer dialect, which implies fighting. Kuc made several attempts to get Riek Machar to negotiate with the government with no success.99 Kuc also reported that on the evening before the attempted coup, Oyai Deng Ajak100 said to Thomas Duoth at his house, “we will take the government within two hours because you don’t have professional army, police and neither security.” He explained that Thomas Duoth had told him this.101

13 December 2013, Kuc received a report that Brig. Gen. Peter Lim was distributing money to Nuer soldiers in the Tiger division. Kuc informed Major General Marial as the district commander of the Tiger division.

14 December 2013, Kuc informed Major General Marial on the mobilization of the Nuer forces within the Tiger Division.102

Kuc explained that various meetings took place in the lead up to the attempted coup, including the following:

2 December 2013, A meeting at Riek Machar’s house attended by Riek Machar, Rebecca Nyadeng, Alison Manani, Chol Tong, Oyai Deng and Deng Alor.

3 December 2013, A meeting at Riek Machar’s house where it was resolved that they would conduct a press conference and public rally on 6 December 2013.

13 December 2013, A meeting at Riek Machar’s house attended by Riek Machar, Chol Tong, Pagan Amum and Deng Alor.

16 December 2013, The signal unit of Internal security intercepted Deng Alor requesting Majak De Agot to convince Hilde Johnson to take South Sudan to a similar level as Democratic Republic of Central Africa.103

Major General Lemi Longwonga, Director of Crime Intelligence and Prevention stated that when he returned to South Sudan on 13 December his deputy briefed him on the security situation and told him that there had been abnormal movement of CID personnel which had been undertaken secretly by Colonel Gathon.104 He directed his deputy to write a report on the matter.

By 15 December, his deputy had failed to submit the report. Later that day, he heard shooting around 10pm, went to his office at CID HQ and was told to remain there by the Inspector General of Police.105 Major General Longwonga explained that the security organs were following the political activities of the three groups rivalling for chairmanship of the SPLM in the upcoming National Liberation Council Convention. They followed (i) Riek Machar’s group, (ii) Mama Rebecca’s group and (iii) Pagan Amum’s group. These groups finally reconciled and allowed Riek Machar to be their leader. Longwonga explained that the activities of redeployment of CID personnel by Colonel Gaton are the only indicators of a planned coup in CID. Riek Machar and Taban Deng Gai kept the idea of a coup only with those they trusted. There were reports that Riek Machar had asked Dr Majak to persuade Pagan Amum to join his leadership and convince Mama Rebecca to join him, promising her the vice presidency if she did so.106

Brigadier Awer Nathan, Director of Crime Intelligence and Prevention, told the Commission that at the time of the shooting, his first information was from the CID personnel that there had been regular gatherings of Nuer CID police personnel spearheaded by Col Garton Jal and Samuel Gatkoi. Nathan issued an order removing all rifles from the hands of the forces and putting them in the store except those authorised for duties. Nathan informed the Director of CID about the suspicious Nuer gatherings within the three weeks of December. Notably, Garton and Gatkoi started to absent themselves from work.107

Thomas Duoth Guet, Director General of the External Security Bureau, stated that on 15 December 2013 he attended the house of General Oyai Deng for a dinner party organised by Chollo Youth108 in honour of Johnson Obeny’s109 promotion. Majak De Agot,110 Guier Chawng,111 Taban Deng Gai and Pagan Amum were also present. General Oyai Deng told him he was happy that he was there so that he could personally take the message to the President as to why they boycotted the National Liberation Council conference sessions on the Monday morning. General Oyai Deng said they would denounce the Chairman as he had dissolved all structures of the party. When asked how he would do this, Oyai Deng stated: “you people don’t have a professional army, police and national security. If anything happens, we can control Juba within two hours.” He said they would inform the President that they would go on the street. Taban Deng Gai expressed his anger stating that the President cannot replace the founders of the SPLM-A with new-comers and that he could not be replaced by someone like the current governor of Unity, Josep Monytool [Joseph Monytuil] from the National Congress Party. If things became violent, Deng Gai stated that: “we will control resources. We will control the oil fields and this makes the government ungovernable.”112 Dr Majak De Agot told Guet to “tell the President to solve our problems peacefully, we don’t want to go for violence. Those who are with the president and give him wrong advice are not his people. If it is in that way that the President runs the government, it’s better for us to take the government.”

Guet explained that Guier Chawang was angry about the President replacing him and others who did not contribute in the same way during the struggles. Banguet Amum stated “We are going on Monday to denounce the chairman on 16th December.”113 Guet called the Chief of General Staff and asked him to call the General Director of Security and Commander of Presidential Guards to meet at the house of the Chief General of staff so that he could convey the information he had gathered and arrange for a meeting with the President.114

Honourable Aleu Ayieng Aleu, Minister of the Interior stated that he was aware from the CID, military intelligence and internal security that Riek Machar and supporters from SPLM had been conducting meetings at different houses. They were not aware of the agendas of those meetings. When Riek Machar and his supporters wanted to organise a press conference and public rally, he began to be concerned in his role as Minister of Interior.115 He explained that one day, the representative of the UN, Hilde Johnson came to his office and raised concerns about the current political situation of the SPLM. Aleu told her that he understood the constitutional right to conduct a press conference. It emerged that permission for a press conference to be held by Riek Machar on 6 December had been granted by President Kiir.116

Aleu referred to the press conference conducted on 6 December in which Riek Machar criticised the government and insisted on conducting a public rally. Aleu spoke with Riek Machar and requested him to conduct it at SPLM House if his reasons were genuine. He said that Riek Machar and his SPLM supporters attended the first day of the SPLM Conference on 14 December but boycotted the next day due to growing misunderstanding on the voting mechanism.117 Aleu also stated that there was a significant incident “on the next sessions where an unknown gunman shot a bullet towards the conference hall and people started to leave.”118

15 December shooting started around 9pm at the military barracks of the former Sudan Army Force and that on 16 December when he went to the house of Riek Machar, he had left for an unknown place with Taban Deng Gai. He started to instruct the police to arrest those who participated in Riek Machar’s press conference. “At the meeting at Rebecca House, the issue of toppling the government was raised by Riek but Rebecca and others opposed it.”119

D. Conclusion

The evidence of the telephone intercepts and the Investigation Commission’s inquiry mutually corroborate each other and give a coherent explanation of the causes of the conflict that broke out in South Sudan on 15 December 2013. The conflict was caused by an attempted coup planned by principals – Riek Machar, Taban Deng Gai and Brig. Gen. Peter Lim Bol Badeng. The evidence is credible and authentic. It can be said to justify the position of the Government of South Sudan as it has sought to resist the policies and agenda of the international community that would not accept the explanations advanced on behalf of the state by its President and ministers.

Fig. 1

Location of Giada, Newsite and Bilpham SPLA (SSPDF) HQ

The United Nations, African Union, USA, and EU did not describe the events of 15 December 2013 as an attempted coup. The preferred international response referred to a political crisis that escalated to violence carried out by the military and various armed groups. Ethnicity and political factionalism were named as the overriding causes.120 This narrative enabled prescribed responses to fit a humanitarian agenda. On 20 December 2013, the UN Security Council “expressed grave alarm and concern regarding the rapidly deteriorating security and humanitarian crisis in South Sudan resulting from the political dispute among the country’s political leaders” and concluded that they would “take additional steps as necessary”.121

On 24 December 2013, the UN Security Council issued UNSC Resolution 2132 “Determining that the situation in South Sudan continues to constitute a threat to international peace and security in the region,” exercising its Chapter VII powers. Tension existed between the GoSS and UNMISS due to allegations that the latter had aided the rebels. Hilde Johnson (former Special Representative of the UN Secretary General and Head of UNMISS) acknowledges her contact with Riek Machar on 15-16 December 2013 in her memoir but denies the UN aided him.122 The issue of UN neutrality and its agenda in South Sudan was raised.123

A press statement by President Kiir in January 2014 questioned the role of the UN at this time: “I think the UN want to be the Government in South Sudan and they fell short of naming the chief of the UNMISS as the co-President of the Republic of South Sudan”.124 The Americans intervened to insist on a renewal of relations between South Sudan and the UN and on 24 January 2014 President Kiir issued a press statement ensuring that all foreign nationals and UN staff were protected.125

The EU did not issue an immediate response to the events of 15-16 December 2013. They sent their regional delegation on 26 December and subsequently coordinated efforts through IGAD and the AU. The Americans, who were heavily invested in South Sudan did not refer to the attempted coup. An indirect reference was made by former President Obama on 21 December 2013: “Any effort to seize power through the use of military force will result in the end of longstanding support from the United States and the international

community”.126

However, both UNMISS through Hilde Johnson, and AUCISS were provided with summaries and audio material of telephone intercepts between Taban Deng Gai, military commanders, Riek Machar and other political leaders planning and executing the attempted coup of 15 December 2013 but chose not to conclude that an attempted coup had taken place. This was despite the GoSS aiding international partners in their response efforts and consistently promoting a message of peace and accountability for “criminal” elements who had caused the violence. The Government found its description of events overridden by external powers who chose to pursue an ethnically driven narrative that has informed responses to South Sudan thereafter.

A. The International Response

(i) United Nations

On 16 December 2013, the UN made two public statements regarding events in South Sudan: One appealing for calm127 and the other referring to the humanitarian situation.128 No mention of the attempted coup was made. Hilde Johnson had spoken with senior ministers in the early hours of 16 December who informed her that President Kiir was “managing a crisis”129 and she spoke with him at 05.00.130 Significantly, the words used to describe President Kiir’s activities speak to a situation that was not of his making. Also of significance to the events that took place, is the difference between the actual evidence of Riek Machar’s knowledge of events as revealed in the telephone intercepts and what he stated at the time.

On 17 December 2013, the UN issued highlights from a phone conversation between UN Secretary General, Ban Ki Moon and President Kiir: “Asked whether a coup had been attempted in South Sudan, the Spokesperson said that the Mission was monitoring events, while undertaking its primary task of trying to ensure the safety of civilians affected by the armed violence.”131 The UN was avoiding giving weight to the attempted coup although the interest in whether that was the cause for the conflict is of importance, for the true understanding of events and appropriate actions to take thereafter.

On 17 December 2013, Hilde Johnson admitted in her memoir published after the events that, “what we knew was anecdotal at best.”132 However, Johnson particularly referenced “targeted ethnic killings”. She stated: “what clearly had been at first a fight between forces of the Presidential Guard loyal to the President and those siding with Riek Machar had degenerated into a deliberate massacre of Nuer, and particularly Nuer males.”133 Although references to the coup are made, Johnson focused on politics and ethnicity as root causes and consequences of the violence. In doing so, Johnson avoided the significance of the cause of the fighting if the events of 15 December 2013 were indeed triggered by a coup. There is no supportive evidence that the conflict that took place was ethnically motivated, whereas the political alignments that were the cause for the conflict are clear.

Johnson criticised President Kiir for his press briefing of 16 December claiming he did not “explicitly order his forces to protect civilians or express regret for those killed”134 and that: “After this we could expect no call for restraint from Riek.” This statement bears close consideration as it is language aimed at tainting President Kiir’s conduct and by inference suggests he was responsible for attacks upon civilians and the targeting of Nuer males. The evidence in this report establishes Machar had caused the conflict in the first place. In fact, President Kiir’s press statement of the morning of 16 December 2013 only tried to reassure citizens that the government was in control of the security situation and condemned the “criminal actions” of forces loyal to Riek Machar. A curfew was ordered and he reiterated the SPLM’s commitment to the peaceful transfer of power and the priority of the security and safety of citizens. President Kiir also stated he would not allow the incidents of 1991 to repeat themselves again and condemned criminal actions. The reference in the statement to 1991, were subsequently taken as provocative, rather than anger at events that should not have been repeated. Johnson seems to fail to appreciate the significance to those involved in the government of the implications of a military coup taking place at the time.

In a press conference on 18 December 2013, the UN’s Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon referred only to the “political crisis”, requiring “political dialogue.” UNMISS issued a press statement on 18 December calling on the “Government of South Sudan to do its utmost to end any continuing violence …UNMISS calls on all parties to the violence to exercise restraint and seek a peaceful way out of the current crisis.”135

These exhortations need to be considered in context where there is a conflict as a result of an attempted coup. All the government can do is to challenge the forces seeking to usurp it from power by armed force and engage with legal processes once it has control of the situation – if that is the outcome.

Johnson met with President Kiir on 18 December where she called on him to order the halt of all ethnically motivated violence. The President reassured Johnson in respect of her concerns and stated that he was committed to redoubling his efforts and holding those accountable for their criminal actions.136 He informed her that he had met with Nuer leaders the previous day to clarify “misleading information” that the Nuer were being targeted as a community.137 Throughout, President Kiir declared that the ‘crisis’ was executed by the criminal actions of a few and stated he was committed to restoring peace. He did not refer to ethnicity and spoke of the citizens of South Sudan. The narrative from Johnson and the UN was at odds with the knowledge and information of the government.

Parallels were drawn at the time with Rwanda from international staff138 and Johnson also admits to the influence of Majak d’Agot’s warning to her “this could become another Rwanda”. The impact of these resulting biases was apparent.139 Johnson’s expectation that President Kiir should order forces to halt ethnically motivated violence as a result of her own contextualisation of events, when he was dealing with an attempted coup, led to the promotion internationally of the ethnic conflict narrative rather than its political source.

On 19 December, President Kiir gave a press conference calling for calm, confronting tribalism and the arrest and trial of anyone found attempting abuse, looting or killing.140

However, basing their conclusions on UNMISS reporting, on 19 December 2013, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay issued a statement which focused on extrajudicial killings141 and targeted ethnic killings. Johnson used these references to describe the events of December 2013 in her 2016 memoir.142 She also stated at this time: “In the Mission, we remained unconvinced that an attempted coup had taken place.”143 This conclusion of course was made without access to the facts at the time, and it set in train an UNMISS-led narrative of ethnically targeted attacks and rejection of the coup attempt as each international institution took up the cause.

This in turn, called into question the legitimacy of the actions of the GoSS in the context of the conflict. Johnson and the UN’s need to be ‘convinced’ that an attempted coup had taken place in order to accept statements made on behalf of the government and the President is plainly wrong.

On 20 December 2013, the UN Security Council condemned the targeted violence against civilians and specific ethnic communities144 and on 24 December 2013, the Security Council further condemned what it described as ethnic violence perpetrated by both armed groups and national security forces.145 UN Security Council Resolution 2132 on 24 December 2013 called on President Kiir for an immediate end to the violence and urged “Riek Machar and his forces to rise to the challenge of nation-building.”146

UNMISS’s Interim Report from 21 February 2014 included reference to President Kiir’s claims of a coup attempt but did not pursue matters further with GoSS to establish the basis as to why it claimed it was the cause for the events that took place on 15 December 2013. The final report from 8 May 2014 referenced President Kiir’s press conference of 16 December 2013 and allegations of an attempted coup as well as the status of the political detainees for their “purported coup attempt” 147 but did not include in its findings the cause of the violence.

Hilde Johnson states she saw summaries of the audios of Taban Deng Gai organising troops and weapons supplies prior to the coup but questioned their authenticity.148 She remained ‘unconvinced’ of a coup and based on her memoir references, did not pursue analysis or review of the materials further to understand them. The narrative that was preferred by her for the events that took place could be said to have had great influence upon the policies pursued by the UN and other international institutions in their dealings with, and treatment of, South Sudan at the time and thereafter.

(ii) African Union (AU)

On 30 December 2013 at its 411th Meeting, the Peace and Security Council of the African Union mandated the establishment of the AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan (“AUCISS”). Its mandate was to investigate human rights violations and other abuses committed during the armed conflict; investigate the underlying violations and make recommendations to ensure accountability, reconciliation and healing and in moving the country forward in unity, cooperation and sustainable development. A report was to be submitted within three months. The Commission’s four focal areas were: healing, reconciliation, accountability and institutional reforms. The AUCISS was formally created on 7 March 2014.150

The temporal jurisdiction of the Commission began from 15 December 2013 – the day the hostilities broke out. However, the reconciliation, healing and institutional reform aspects of the mandate were not time bound.

The communique issued by the AU mandating AUCISS, did not refer to a coup but paragraph 5 – which reiterated the “AU’s relevant instruments on the rejection of unconstitutional changes of Government and the use of force to further political claims,”151 – did draw upon President Kiir’s press statement of 16 December 2013 for its message regarding the peaceful transition of power.

The 30 December communique outlined the willingness of President Kiir to engage in peace talks and the absence of Riek Machar at the table stating that: “The Council endorses the IGAD Summit decision that face-to-face talks should commence by 31 December 2013. In this regard, Council welcomes the expressed commitment of President Salva Kiir to engage in talks unconditionally and looks forward to Dr. Riek Machar and other stakeholders concerned to do the same.”152

In the subsequent African Union Commission of Inquiry established on 12 March 2014, President Kiir gave two interviews in which he explained the genesis of the conflict and the nature of the coup attempt.153 In its report, issued on 15 October 2014,154 the AU rejected the claims of President Kiir, determining there was no coup attempt.155 The detail of what President Kiir told the AU bears close scrutiny in the context of the information provided to them in respect of the telephone intercept evidence disclosed in this report in Chapter 1.156

The intercepted phone calls evidencing the coup were submitted to AUCISS by the former Director General for Internal Security, Major General Akol Koor Kuc.157 In his interview the General informed the Commission of voice intercepts, “of Taban Deng manning the situation and asking those with whom he was in contact if they had accessed the guns as well as mobilising the youths who had been trained around the mountains because they were not armed.”

He even asked the youth “have you got the guns”?” However, the Commission having listened to the intercepts stated it, “could not detect information relating to a coup from the intercepted conversation they listened to”.158 The Commission did not attempt to clarify further with the GoSS the content of the intercept evidence. If it had, it would not have made the findings below.

AUCISS disbelieved the GoSS account of the 2013 conflict and rejected President Kiir’s statement of facts of the violence with these words, “there are two competing narratives. The first holds that the violence was sparked by disagreement within the Presidential Guard following a claim that there was an order to disarm sections of the Presidential Guard. The second narrative which emerged on December 16th 2013 was that the violence was sparked by an aborted coup. From all the information available to the Commission the evidence does not point to a coup.”159 (Emphasis added) The expression “aborted coup” was not even the correct context of the GoSS submission – that it was a planned coup.

The rejection of the account of President Kiir and supporting witnesses for GoSS has had a significant impact. The AUCISS final report is viewed as the ‘truth’ of what happened in December 2013; yet, even Hilde Johnson questions the reliability of some of its findings: “This included me, as sentences from a background briefing for the AU Commission had been used as an interview without my knowledge and consent, out of context and given different meaning. Similar things happened to others, who found themselves inaccurately quoted with their full names and without their consent.”160 This report undermined President Kiir’s testimony and gave higher credence to international staff who admit at the time that what they knew was “anecdotal at best”.

The AU Commission employed both primary and secondary data collection methods to inform its report. Limitations in accessing certain areas and key individuals presented challenges to the Commission, along with lack of access to documentary evidence such as medical records and statements. A notable absence of information was UNMISS’s data which they claimed to have been recording since December 2013. From Johnson, we know however, that information collection was difficult to corroborate. The AU team therefore relied on “witness statements, physical evidence and documentary data availed to the team to reconstruct the events, obtain a forensic analysis and opinion of the events and make valuable conclusions thus meeting its objectives.”161

The African Union also did not refer to an attempted coup in its press statements in December 2013. The AU’s response on 17 December 2013 referred to a “deep concern, [for] the situation in South Sudan, marked by an outbreak of fighting in parts of Juba, since the evening of Sunday 15 December 2013”.162 On 16 January 2014, the Peace and Security Council for the AU referred to the Council’s reiteration of “its grave concern at the escalation of the political dispute in South Sudan into a full-fledged civil war.”163

(iii) Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD)

IGAD were at the centre of peace mediation and conflict resolution efforts in South Sudan. Contrary to Hilde Johnson’s perception of him, President Kiir welcomed the assistance of IGAD and a high-level ministerial delegation travelled to Juba between 19-21 December, with senior AU and UN representatives, urging an immediate cessation of hostilities. President Kiir committed himself to “unconditional dialogue; cessation of hostilities; use of IGAD good offices to contact Dr. Riek Machar and the opposition; protection of the civilian population and humanitarian workers by the GoSS armed forces; maintaining the dispute at political level and preventing it from escalating into an ethnic or tribal conflict.”164

In a communique issued on 27th December 2013, IGAD made reference to “all unconstitutional actions to challenge the constitutional order, democracy and the rule of law” and in particular, it condemned “changing the democratic government of the Republic of South Sudan through use of force.”165

On 4 January 2014, IGAD announced the start of direct talks in Ethiopia “between the parties to the conflict in South Sudan.” The press statement noted that: “The parties must use these talks to make rapid, tangible progress on a cessation of hostilities, humanitarian access and the status of political detainees.”166

(iv) USA

The Americans played a major role in how the international community received and responded to the situation in South Sudan.

Ezekiel Lual Gatkuoth (EG) played a key role in communicating disinformation to the US, to whom he was connected as a former Ambassador of South Sudan.167 Gatkuoth was an insider on the coup attempt and what he said in a phone call to US Ambassador Susan Page (SP) on 16 December 2013 at 01.09.42168 reinforces the coup attempt:

EG: You know the people who were fighting…One group took the Presidential Guard Headquarters.

SP: What do you mean they took the Presidential Guard Headquarters?

EG: That’s what I mean, the National Security Headquarters.

SP: Sorry what do you mean by that, they took…who took what? Headquarters?

EG: I think those who were fighting amongst themselves, one party chased others

SP: I’m sorry…I don’t know why the connection is not very good. Say that again…

EG: I want to be vague like that…I don’t know…(laughing) because they are just giving me information…calling…calling…

SP: OK…

EG: Yeah…so…