The government of South Sudan’s response to the Sentry’s report “Undercover activities: inside the national security service’s profitable playbook”

Return Home

Return Home

Demand to Withdraw The Report from Circulation and to Issue Public Apologies to the Named Individuals and Companies

The Government of South Sudan (‘GoSS’) demands the immediate withdrawal from circulation of The Sentry’s publication “Undercover Activities: Inside the National Security Service’s Profitable Playbook” (the ‘Report’) and the issuance of a public apology to each and every individual, company or entity that has been falsely or misleadingly described in the Report.

The Publication

The Report purports to be a fact-based document with commentary that has been widely disseminated internationally and contains false and/or misleading allegations that have either been made deliberately or recklessly. The intended recipients of the false and/or misleading information published by The Sentry are: international agencies such as the United Nations and its satellite organisations; states such as the USA, UK, Canada, Australia; collections of states such as the EU, AU and other international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, international and national NGOs, international and national media, and political parties in South Sudan and elsewhere that use such disseminated information to determine or advocate political, economic and/or development strategies for South Sudan and its people. The list of so-called Recommendations at the end of the Report in which The Sentry seeks targeted sanctions, seizure of assets and notice of financial risks amongst many other measures, reveals its purpose of causing economic damage and harm to those falsely and/or misleadingly named, which in turn harms the development of South Sudan.

The GoSS’s forensic review of the sources and evidence relied upon in the Report reveals that allegations have been made that are false, misleading and based on incorrectly interpreted and out-of-date information obtained pursuant to a serious data breach. The Report is based upon flawed methodology and draws on second-hand hearsay (including click-bait and newspaper articles), generic references to document collections, self-referential material and anonymous sources, all of which prevent proper scrutiny of the serious allegations made against both individuals and the National Security Service (‘NSS’).

The False, Misleading and Incorrect Allegations

The Report makes serious and wide-ranging allegations that NSS members have been able to “access off-budget finances and diverted revenues, all while side-stepping oversight and operational scrutiny.”1 The Report alleges that there is a “vast network of companies with NSS shareholders, ranging from media and publishing to natural resources and logistics. The oil, finance and media sectors particularly suffer from NSS involvement both in terms of economic capture and repression.”2 The Report claims to have identified “125 companies…[with]…NSS shareholders.”3 Not all these companies are named within the Report.

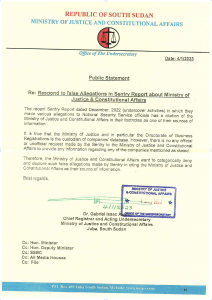

Citing South Sudan’s Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs (‘MOJCA’) as the source for 16 footnotes,4 the GoSS confirms that no official contact has in fact been made with MOJCA as set out in its public statement dated 4th January 2023 (Annex 1). The data breach of disclosure of out-of-date records is currently under investigation in South Sudan.

The methodological failings of the Report reveal a lack of investigative rigour, the recycling of information without independent research and misjudgement in making the most serious of allegations of wrongdoing based on false, misleading and incomplete information that was either deliberate or reckless. In one instance for example, no substantive information was cited to underpin the most serious of recommendations, namely the sanctioning of a named individual, Mr Jalpan Obyce, whose reputation has now been tarnished.5 In another instance, the Report recycles a so-called “well-exemplified” case cited by the United Nations Panel of Experts, that is flawed and misrepresents the true facts concerning Brigadier General Malual Dhal Muorwel and 25 others.6

The GoSS is aware that a significant number of individuals named in the Report have issued letters of complaint to The Sentry, providing corrective information. These letters, many of which threaten legal action, are appended to this Report.

Remedy

The GoSS demands the withdrawal of the Report from public circulation and the issuance of public apologies to the individuals, companies and entities affected.

This Response does not seek to address all the allegations made by The Sentry, many of which are generic, based on anonymous sources or second-hand hearsay, but rather it focuses on those aspects which specifically call into question the actions of named individuals and companies on the basis of information which has been brought to the Government’s attention of serious errors and misrepresentations, in respect of which the GoSS seeks to make a timely response.

As a non-governmental investigative and policy organisation co-founded by George Clooney7 and John Prendergast8 in 2015, one of the stated aims of The Sentry is to “disable multinational predatory networks that benefit from violent conflict, repression, and kleptocracy.”9 The Sentry claims, to “provide evidence and strategies for governments, banks, and law enforcement to hold the perpetrators and enablers of violence and corruption to account.” 10 In doing so, it purports to work in partnership with local and international civil society organizations, journalists, and governments,11 relying on open-source data, field research and what it refers to as “state-of-the-art network analysis technology.” 12

The GoSS notes the serious concerns and complaints which have been raised in recent months about the methodology of The Sentry’s report writing and the making of serious allegations on the basis of questionable evidence.

In December 2022, The Sentry withdrew a report from circulation (alleging the corruption of a Sudanese businessman) after proceedings were commenced against The Sentry for libel and slander in a Sudanese Court. 13

In the same month, The Sentry’s report “Gaming the System: How a Canadian Mining Giant Undermined the Law in DRC”14 elicited a detailed and damning rebuttal of the accusations made against the company Ivanhoe Mines.15 Its response was heavily critical of The Sentry claiming that its findings were “irresponsibly framed to infer or theorize corporate malpractice” and that the report “lack[ed] any tangible evidence that misconduct occurred.” Ivanhoe continued that the report was “rife with misleading content that selectively disclosed supposed facts.”16 It accused The Sentry of “fundamentally misunderstanding” the legislative framework under the DRC mining code and remarked that “it is not clear whether any person qualified to practice law in the DRC, or with any experience in the country, assisted Sentry in understanding DRC mining and company law.”17 Ivanhoe accused The Sentry of “omitting fundamental context” and stated that “the report relies heavily on a myriad of technical legalese intended to infer some nefarious “gaming” of the system. …Sentry failed to understand the Congolese legal framework it now purports to have exposed.”18 It accused the report of “framing the facts for the conclusion that it intends – [and]… presents readers with a nearly impenetrable conspiracy theory-like web of legal transactions.”19 Ivanhoe claimed that The Sentry “ignore[d], in this case, the qualification and experience of [Ivanhoe] and the lawfulness of the process, to continue to hold its conclusion rather than considering that there are logical, rational and legal explanations for commercial events.” Ivanhoe concluded its response by inviting The Sentry to meet with them. It is not clear whether this meeting ever took place. As of 27th February 2023, the DRC Report is still published on The Sentry website.

In sum, Ivanhoe held that The Sentry was guilty of confirmation bias. The GoSS has identified similar serious methodological flaws in the current Report.

The methodological flaws which undermine the credibility and reliability of the Report are set out below.

i. No Opportunity for the NSS to Respond to the Serious Allegations Prior to Publication of the Report

No individual from within the higher echelons of the NSS was contacted during the preparation of the Report. Neither was the NSS as an institution provided with an opportunity to comment on the draft allegations before publication. This is despite The Sentry’s own stated principles of endeavouring to contact “the persons and entities discussed in its reports” to “afford them an opportunity to comment and provide further information.”20

ii. Use of Anonymous Sources

While it is accepted that NGOs do not seek to evidentially support their reports to a ‘criminal’ standard of proof, the overuse of anonymous sources denies those accused of being able to interrogate the reliability and credibility of the information and thereby challenge what has been alleged, particularly in circumstances where grave recommendations are made, namely the imposition of sanctions against named individuals.

The Report’s footnotes reveal that only two named individuals were ‘interviewed’ for the purpose of the Sentry Report21 and two others were communicated with, along with a Kenyan law firm, during the Report’s preparation.22 The other cited individuals remained anonymous. An analysis of the sources shows that eleven footnotes in the report are based on information from one unnamed civil society activist.23 Six footnotes are based on information from an unnamed journalist.24 Four footnotes rely on information from an unnamed oil sector employee.25 An unnamed human rights analyst/South Sudan expert26 and an unnamed employee of the National Revenue Authority27 are also relied on as sources.

Such use of anonymous hearsay prevents any interrogation of the credibility and reliability of the sources. Reliance on this type of source prevents those accused from answering back.

This lack of investigative rigour subsequently exposes the UN, States, international and national organisations to the risk of being manipulated by such reports to impose sanctions with far-reaching consequences for both individuals and companies. In this instance, The Sentry has called, in a quasi-authoritative way, for international punishments to be meted out to individuals named in the Report.

iii. Circularity of Source Reliance

The Sentry Report suffers from a circularity of source reliance on third-party hearsay reports from institutions employing a similar stance towards South Sudan (e.g. UN, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, Global Witness), the bases for which have crucially not been independently verified by The Sentry. Just under a third of the footnotes rely on such sources.

There are 12 references to a single Human Rights Watch report.28 The bulk of these references make up the main source of generic allegations against the NSS with no specificity or context. Most, if not all the (mostly ‘one-line’) allegations drawn from the Human Rights Watch report can be found in the report’s initial short summary. In turn, the Human Rights Watch report also relies in part on third-party research without independent verification.

The Global Witness 2018 report29 is referred to 7 times in the Report, and contains interviews with unnamed sources, referencing again Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and UN reports.

6 Amnesty International (‘AI’) reports are cited in the Report.30 Of these, only 2 are substantial reports31 while the rest are single-page campaign briefings. Neither of the substantive reports are fleshed out or referred to more than once in the Report. Indeed, the single-page briefings appear to be the main source of allegations in the Report. It is notable however that these single page AI briefings contain no footnotes or references to substantiate the allegations they make. The AI allegations were taken by The Sentry as confirmed facts, and it is not apparent from the Report’s referencing that they were subjected to any further investigation or verification.

iv. Reliance on Other Sentry Reports

There are 19 references to 5 other Sentry reports32 (without any reference to specific sources or paragraphs) as well as reports published under other outlets by a senior member of The Sentry’s staff.33 This self-referential approach to evidence collection is sub-standard and lacks appropriate investigative rigour, particularly given the methodological flaws identified in the Report, which now calls into question the accuracy and reliability of investigations conducted more widely by The Sentry.

v. Heavy Reliance on Open-Source Media Reports

The heavy reliance on open-source media reports constitutes nearly 20% of all sources cited.34 The veracity of such hearsay reports cannot easily be verified and are open to bias. Only two media organisations of those cited are accredited in South Sudan, namely Eye Radio35 and Juba Monitor.36 Six of the footnotes refer to the US platform Voice of America, which has not renewed its licence with the Media Authority in South Sudan and over a half of the open-source media footnotes refer to foreign online outlets, with the majority focusing on maximising viewers through the use of sensationalist, tabloid-style headlines to feed a populist ‘clickbait’ readership.37 The remaining references are to foreign media bodies38 which on the whole reflect a partial reporting to fit a predefined narrative of South Sudan.

vi. Reliance on Generic Document Collections

The Report relies on an “analysis of corporate records cross-referenced with an NSS official list, March 2022.”39 No information has been provided as to the precise nature of the corporate records or the NSS ‘Official List’, their provenance, authenticity, or reliability. The way in which this material has been referenced in the Report prevents independent scrutiny of the information, its accuracy and potential/actual bias. Employing such a basic cross-referencing exercise does not suffice to substantiate allegations of such seriousness.

vii. Reliance on Online Sources Sold for Profit

The Report also relies on ‘Person reports’ cited as Lexis Nexis and Nexus respectively40 LexisNexis reports are merely an amalgamation of public filings on a person taken from online sources and sold for profit. As they are data capture reports rather than ‘produced’ reports, their accuracy is unverified and likely to be unreliable.41

viii. Data Breach – No Official Request for Information from South Sudan

Most of the allegations made in the Report concern the activities of companies over which it is alleged the NSS has achieved ‘State Capture’ by involvement of its members as shareholders or directors.

In a Public Statement dated 4th January 2023, MOJCA stated that while it was true that the Ministry “and in particular the Directorate of Business Registrations is the custodian of companies’ database, no official or unofficial request was made by The Sentry to the Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs to provide any information regarding any of the companies mentioned.” The Ministry letter went on to state that it categorically denied being Sentry’s “source of information.” See Annex 1.

The information relied on is misleading, incorrect and was not obtained pursuant to official procedures for obtaining data on companies registered in South Sudan.

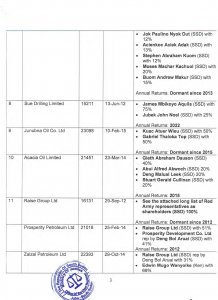

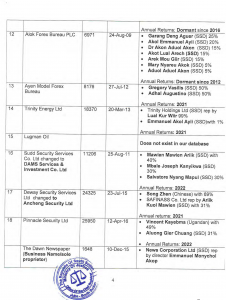

The GoSS’s analysis has found that the Report (i) falsely mischaracterises individuals as members of the NSS, (ii) does not correctly present the nature of the involvement of NSS members in companies and most crucially, (iii) fails to note that a significant number of the companies mentioned have been dormant for 8-11 years.

In South Sudan, the rules concerning dormancy of a company are set out in s.325(1) of the Companies Act 2012, which provides as follows:

“Where a company has been dormant from the time of its formation or has been dormant since the end of its previous accounting period and is not required to prepare group accounts for that period, the company may, by a special resolution passed at a meeting of shareholders of the company at any time after copies of the annual accounts and reports for that year have been duly sent to shareholders, declare itself to be a dormant company.”

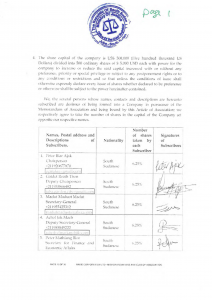

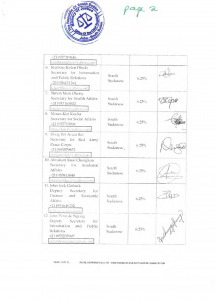

Under the Companies Act 2012, the Minister of Justice holds the responsibility for corporate affairs and a Registrar of companies is appointed to keep the records and supervise their administration as required by the Act. The inspection of documents held by the Registrar and any certificate of incorporation or copy of any other company document can be undertaken upon payment of a prescribed fee.42

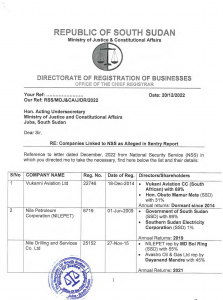

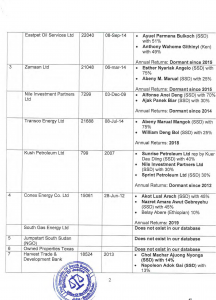

In response to The Sentry’s report, on 20th December 2022, the Directorate of Registration of Businesses issued a letter setting out Company names, Registration Numbers and the names of Directors and Shareholders, including information about the dormant status of the relevant companies.

i. Non-Executive Directorships

Akol Koor Kuc and Nilepet

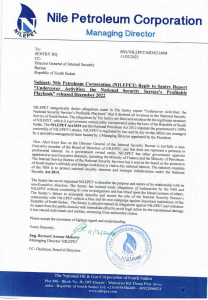

In his response to The Sentry in February 2023, Mr Bernard Amour Makeny, the Managing Director of NILEPET categorically denied the allegations made in the Report that the company diverted oil revenues to the NSS. See Annex 2.

He stated that the allegations made were false and misdescribe the legitimate structure of NILEPET, which is a government-owned entity, incorporated under the laws of the Republic of South Sudan and regulated by law. Mr Makeny explained that NILEPET’s day-to-day affairs are managed by a “specialist management team headed by a Managing Director appointed by the President.” He stated that “Hon Akol Koor Kuc as the Director General of the Internal Security Bureau is lawfully a non-Executive member of the Board of Directors of NILEPET, and this does not represent a personal or preferential interest. As a government owned entity, NILEPET has other governmental agencies appointed as non-Executive directors, including the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Petroleum. The Internal Service Bureau of the National Security Services has a seat on the board as the protection of South Sudan’s oilfields and foreign workforce is vital to the national interest. The statutory mandate of the NSS is to protect national security interests and strategic infrastructure under the National Security Act 2014.”

Mr Makeny explained that The Sentry had never “requested NILEPET to describe the purpose and nature of its relationship with its non-Executive directors. The Sentry has instead made allegations of malpractice against the NSS and NILEPET without conducting its own investigations and has relied upon the biased sources of others.” He stated that “The Sentry’s failure to accurately describe and record the role of the Internal Security Bureau’s relationship with NILEPET reflects a bias and its own campaign against important institutions of the Republic of South Sudan.”

Mr Makeny asks The Sentry to “retract its allegations against NILEPET and withdraw its report from the public domain with immediate effect to avoid legal action for the reputational damage it has caused individuals and entities, stemming from unfounded claims.” To date, Mr Makeny has not received a response from The Sentry.

ii. Not a Shareholder or Director

Misleading and false information contained within The Sentry’s Report extends to the wrong attribution of positions to individuals within oil companies as set out below.

Manasa Machar Bol, Kush Petroleum Ltd, Transco Energy Ltd, Zamaan Ltd & Nile

Investment Partners Ltd

The Report made the following allegations against Mr Manasa Machar Bol:

“Manasa Machar Bol, an NSS officer and the Director of Oil Security in the Ministry of Petroleum, has been a beneficial owner of two oil companies: Transco Energy and Kush Petroleum. Bol’s ownership in Kush Petroleum was through Nile Investment Partners. Kush Petroleum supplies petroleum for numerous companies, airlines and NGOs, including the UN World Food Programme. In 2014, it received two letters of credit totalling over $2 million to supply fuel and petroleum products. Oil export data reviewed by The Sentry could only account for approximately $150,000 worth of fuel being imported by Luqman Oil, the company that Kush Petroleum contracted with for delivery.”

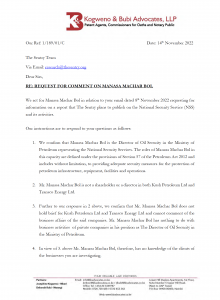

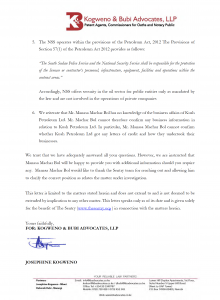

On 8th November 2022, in answer to questions from The Sentry, Mr Bol’s lawyers, Kogweno and Bubi Associates LLP provided a series of substantive answers to the allegations made by The Sentry. Mr Bol’s lawyers explained that Mr Bol is the Director of Oil Security in the Ministry of Petroleum representing the National Security Services. His roles are defined under Section 57 of the Petroleum Act 2012 and include the provision of adequate security measures for the protection of petroleum infrastructure, equipment, facilities and operations.

The letter also explained that Mr Bol is not a shareholder or a director of either Kush Petroleum Ltd or Transco Energy Ltd. He does not ‘hold a brief’ for either company and therefore, cannot comment on the business affairs of the said companies. He has no role in respect of “private companies in his position as The Director of Oil Security in the Ministry of Petroleum.” The letter confirmed that Mr Bol has no knowledge of the clients of the businesses being investigated. He was not therefore in a position to “confirm any business information in relation to Kush Petroleum Ltd.” Neither could he confirm “whether Kush Petroleum Ltd got any letters of credit and how they undertook their business.” None of this information provided was used or referenced in the Report.

The letter explained that the NSS operates within the provisions of the Petroleum Act 2012, s57(1), which provides as follows: “The South Sudan Police Service and the National Security Service shall be responsible for the protection of the licensee or contractor’s personnel, infrastructure, equipment, facilities and operations within the contract areas.”

The letter states that “NSS offers security in the oil sector for public entities only as mandated by the law and are not involved in the operations of private companies.”

In a second letter to The Sentry, dated 24th November 2022, Mr Bol’s lawyers informed The Sentry that their client is “neither a director nor a shareholder in Zamaan Ltd and Nile Investment Partners Ltd.”

The Sentry was provided with extensive answers to questions raised about the alleged involvement of Mr Bol in four oil companies and omitted publication of his detailed response in advance of publishing the Report, preferring instead to insert a one-line denial of the allegations which failed to reflect the detail of the individual’s position.43 The Sentry persisted in the publication of its allegations. See Annex 3.

Ter Tongyik Majok, Raise Group Ltd, Prosperity Petroleum Ltd and Zalzal Petroleum Ltd

Under the heading ‘Profitable Connections’ and in the context of alleged ‘Economic Capture’ by members of NSS of the oil sector, Ter Tongyik Majok’s name is included in an organigram in The Report44 alleging that he was the Director of Raise Group Ltd and a shareholder of Prosperity Petroleum Ltd and Zalzal Petroleum Ltd. Mr Majok was not contacted by The Sentry to verify its sources before publication.

In his statement to The Sentry, Mr Majok states that “as an individual, I do not own a company nor registered any company in South Sudan that is associated with such names and I do not have shares as alleged.” He requested correction of the Report and an apology. To date, he has received neither. See Annex 4.

Furthermore, the Directorate of Registration of Businesses issued a letter on 20th December 2022 setting out Company names, Registration Numbers and the names of Directors and Shareholders. This document confirms that Ter Tongyik Majok was neither a director nor a shareholder of any of the three companies cited by The Sentry. See Annex 5.

iii. Dormant Companies

Deng Malual Leek & Acacia Oil Ltd

Mr Deng Malual Leek is a South Sudanese national and a businessman. The Report alleged that he was a member of NSS while holding shares in Acacia Oil Ltd.45 Both Mr Leek and the company were cited in an organigram in the Report, entitled ‘Profitable Connections.’

In his letter of complaint to The Sentry, he explained that he has “no link, connection and association with the National Security Service of South Sudan.” He states that Acacia Oil Ltd is a private company incorporated under the laws of South Sudan, in which he has shares. The company “has not transacted any business since its incorporation and this data is available in public records.” His complaint describes the Report as “inaccurate, unreliable and lacks credibility.” The Sentry “has provided no evidence that even supports its allegations and has misrepresented the ownership and links of a dormant company.” See Annex 6.

Kuac Atuer Wieu & Junubna Oil Co Ltd (Dormant since 2015)

The Sentry alleged that Mr Kuac Atuer Wieu was a shareholder in Junubna Oil Co Ltd engaged in economic capture of the oil sector by NSS members. Both Mr Wieu and Junubna Oil Co Ltd were cited in an organigram in the Report, entitled ‘Profitable Connections.’

On 17th December 2022, Mr Wieu wrote a letter of complaint to The Sentry seeking the retraction of the report and a public apology. He explained that in 2014, he and a colleague registered Junubna Oil Co Ltd to bid for a contact in the energy sector, in his private capacity in the hope of supplementing his “meagre government salary.” Such attempt did not however go beyond registration due to a lack of capital to operationalize the company. The company’s operational documents could not be renewed, and it ceased to function three months after registration.

Crucially, Mr Wieu was never contacted by The Sentry in respect of this matter and no clarifications were ever sought prior to publication of the Report which has in turn damaged his reputation and standing amongst his community. Neither did The Sentry request details about the company from the Registrar of Companies who could have provided the relevant information. See Annex 7.

Emmanuel Akol Ayii Madut (Dormant since 2012)

The Report alleges that Emmanuel Akol Ayii Madut “has been a shareholder in Alok Forex Bureau.” This statement was made under the heading ‘Financial Sector’ in the context of allegations that “The NSS is also involved in critical aspects of the financial sector, from taxation and revenue collection to banking and foreign exchange. Its capture of revenue streams and government institutions allows the NSS to operate without concern for accountability and ensures a constant source of funding for their operations.”46

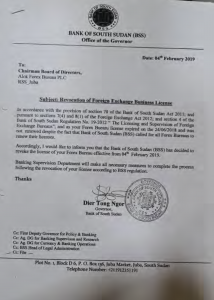

In his letter of complaint to The Sentry dated 6 January 2023, he explained that while he did participate as a shareholder upon formation of Alok Forex Bureau, the company ceased its operations, and the Central Bank of South Sudan revoked its licence in accordance with its respective regulations. Mr Madut stated that he subsequently relinquished his shareholding in the company and placed on record that Alok Forex Bureau’s operations had no direct or indirect shareholding or affiliation with the NSS or any of its members. A letter from Dier Tong Ngor, Governor of the Bank of South Sudan dated 4th February 2019 confirms that the Alok Forex Bureau licence expired on 24th June 2018 and was not renewed. See Annex 8.

Furthermore, the Directorate of Registration of Businesses’ letter dated 20th December 2022 confirms that the company has been dormant since 2012. See Annex 5. Mr Madut was not contacted by The Sentry prior to the publication of the Report. In his letter, he requested The Sentry to retract the allegations, issue a public apology and examine the corporate records. The Sentry’s “wanton disregard for truth and good faith” has sought to “tarnish” Mr Madut’s reputation. See Annex 8.

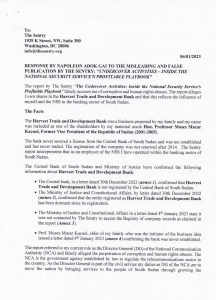

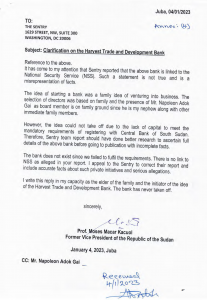

Napoleon Adok Gai and Harvest Trade & Development Bank (Dormant since 2013)

The Report alleges that “The NSS is also involved in critical aspects of the financial sector, from taxation and revenue collection to banking and foreign exchange. Its capture of revenue streams and government institutions allows the NSS to operate without concern for accountability and ensures a constant source of funding for their operations.”47 Specifically, The Sentry makes allegations against Napoleon Adok Gai and alleges that as the Director-General of the National Communications Authority, he is a “shareholder in Harvest Trade and Development Bank.”48 Despite holding a public position, Mr Gai was not contacted by The Sentry prior to publication of the Report.

In his letter to Sentry dated 6th January 2023, Napoleon Adok Gai labelled the report “defamatory”, causing him “considerable distress” and that it has “brought his name into public scandal and odium.” The allegations against him are manifestly untrue and seek to misrepresent his influence in the banking sector. Mr Gai explains that Harvest Trade and Development Bank was a business proposed by his family and that his name was included as one of the shareholders by his maternal uncle, Hon Professor Moses Macar Kacuol, the Former Vice President of the Republic of Sudan (2001-5). He states that the bank “never secured a licence from the Central Bank of South Sudan and was not established and has never traded. The registration of the company was not renewed after 2014.” See Annex 9. Both the Central Bank of South Sudan and MOJCA have confirmed Mr Gai’s information. In particular, the Central Bank confirmed that Harvest Trade and Development Bank is not registered with the Central Bank of South Sudan. While MOJCA confirmed that the entity has been dormant since its registration and that it had not been contacted by The Sentry to access the Registry of Company Records as claimed in the Report.

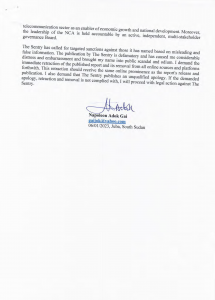

In addition, Mr Gai’s maternal uncle Professor Moses Macar Kacuol, who initiated the business idea, provided a letter dated 4 January 2023, confirming that the bank had never been established. See Annex 10. In his role as Director General of the National Communication Authority (NCA) and as a member of the civil service, Mr Gai stated that his duty is to “serve the nation by bringing services to the people of South Sudan through growing the telecommunication sector as an enabler of economic growth and national development. The NCA is held accountable by an active, independent, multi-stakeholder governance Board.”

Mr Gai has called for the immediate retraction of the Report and its removal from all online sources and platforms. He has also demanded an unqualified apology. To date, he has not received a response from The Sentry.

In a further allegation against Mr Gai, The Sentry asserts that “Gai is also currently the director-general of the National Communications Authority and has in the past been accused of “illegally” and “unlawfully” monitoring the phone communications of those suspected to be working against the government.” 49Two footnote sources are cited, one of which provides no support whatsoever for the allegation.50

The second source is a newspaper report from 2016 from The Sudan Tribune, referring to a case in the High Court where Mr Gai as a witness had applied to have his identity concealed in relation to his work monitoring phone communications of individuals alleged to have been working against the GoSS. This related to the trial of sixteen individuals who were being tried for embezzlement of public funds from the Office of the President including the Chief of Staff of the President. Fourteen of the accused were convicted.

The Defence challenged the admission of the evidence as it had not been authorised at the time by court order. The allegation made by The Sentry against Mr Gai is not set within its proper context. In the trial, the Prosecution and the witness believed the evidence was admissible in the national interest. The Court ruled otherwise and demonstrated the independence of the judiciary. Similar early rulings on matters of admissibility have been made for example in the UK51 and the US52, with the law having since undergone further development.53

Other Companies

In addition to the individuals and companies cited above, five other companies which have been dormant since 2012, 2014 and 2015 and yet they are cited in the Report in the context of “Profitable” and “International” connections, alleging that members of the NSS hold stakes in a number of oil companies, and an aviation company. These dormant companies are (i) Vukanni Aviation,54 (ii) Kush Petroleum Ltd,55 (iii) Eastpet Oil Services Ltd,56 (iv) Zamaan Ltd57 and (v) Nile Investment Partners Ltd.58 The dates of dormancy are set out in the letter from the Directorate of Registration of Businesses’, dated 20th December 2022. See Annex 5. The Sentry failed to obtain up-to-date information in respect of any of these companies.

iv. Misrepresentation of ‘Profitable Connections’ in the Oil Sector

The Sentry alleges that “National Security Service officials hold stakes in a number of oil companies” and thereby have “Profitable Connections.” Letters written to The Sentry since publication by some of those individuals impacted reveal the lack of care taken to interrogate the information relied upon. The Sentry has published serious allegations without seeking to verify or speak with those named in the Report’s organigram. Those named seek the retraction of the Report from the public domain and a public apology.

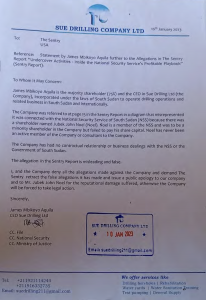

Jubek John Noel & Sue Drilling Ltd

The Report cites Jubek John Noel and Sue Drilling Ltd as examples of the allegation that NSS officials hold stakes in oil companies and thereby enjoy “profitable connections.”

In January 2023, the CEO of Sue Drilling Ltd, Mr James Mbikoyo Aquila sent a letter of complaint to The Sentry to set the record straight. See Annex 11. Mr Aquila explained that while Jubek John Noel is a member of the NSS, Mr Noel failed to pay his share capital and has never been an active member of the company or consultant to the company. Mr Aquila emphasised that “The Company has had no contractual relationship or business dealings with the NSS or the Government of South Sudan.” He demanded that The Sentry retract the “misleading and false” allegations and that it makes “a public apology to [the] company and to Mr Jubek John Noel for the reputational damage suffered” otherwise the Company “will be forced to take legal action.” To date, no apology has been provided.

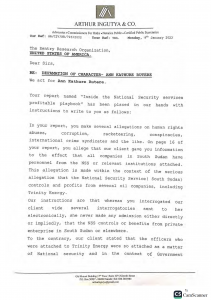

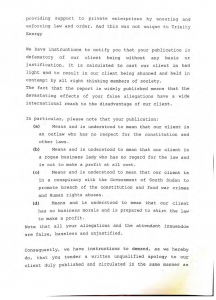

Ann Kathure Rutere and Trinity Energy

In the context of the serious allegation that NSS controls and profits from oil companies, The Sentry alleges that Miss Ann Kathure Rutere gave information to them to the effect that “all companies in South Sudan have personnel from the NSS or relevant institutions attached.”59 The statement sent to The Sentry dated 9th January 2023 from Miss Rutere’s lawyers explains that “she never made any admission either directly or impliedly, that the NSS controls or benefits from private enterprise in South Sudan or elsewhere.”60 The Report does not include Miss Rutere’s explanation that the officers who were attached to Trinity Energy were present as a matter of “National security in the context of the Government providing support to private enterprises by ensuring and enforcing law and order.”61 Miss Rutere’s lawyer demanded a written, unqualified apology and an admission of liability for defamation. To date, neither have been forthcoming. See Annex 12.

In her communications with Sentry prior to publication, Miss Rutere explained that The Sentry could obtain “any information touching on operations and functioning of the Government of South Sudan, a sovereign state, …from that government through the established channels.” She stated clearly that she ceased directorship and operational involvement in Trinity Energy in May 2018. She also set out how she believed that The Sentry were relying on information provided by a former employee allegedly involved in criminal activity, who had a grudge against the company. She explained that it was common practice for companies in different sectors to have an attaché from the NSS, citing hotels, hospitality, media, factories and other corporates including banks. In Kenya, where Miss Rutere is a citizen, she explained that it is also common to have security staff attached to hotels and in many other sectors.

Miss Rutere also reiterated that The Sentry owed both her and the subject companies, “a duty of care not to fabricate…or publish inaccurate, false or malicious information calculated to put [her] and/or the subject companies/entities into disrepute.” She had asked The Sentry to double check the facts before publishing any content, otherwise The Sentry would risk losing its reputation.

Akot Lual Arech, Conex Energy, South Gas Energy & Alok Forex Bureau

Akot Lual Arech is both a South Sudanese and American citizen. He was contacted by The Sentry prior to the publication of the Report, met with researchers and responded to a series of questions sent to him by email. In spite of Mr Arech’s explanation, The Sentry proceeded to publish the “frivolous” allegations against both himself and his wife, Mary Akuel Arech.

Under the heading “Profitable Connections” and in the context of alleged “Economic Capture” by members of NSS of the oil sector, Akot Lual Arech’s name is included in an organigram in The Report62 alleging that he was the Director of Conex Energy and South Gas Energy. It was stated that “Arech’s fellow shareholders in Conex Energy include Kiir’s granddaughter, and until August 2014, the president’s daughter, Adut Alva Kiir, owned shares in the company.”

It also alleged that Mr Arech “had been a shareholder in Alok Forex Bureau alongside inter alia his wife, Mary Kuel Arech.” The Sentry claimed that “Arech was Kiir’s person secretary” and that “he told The Sentry that the president calls him “uncle”, an indication both of respect and of a community relationship.”

In relation to Conex Energy, Mr Arech explained to The Sentry that during the formation of the company, he was invited to be among the signatory shareholders but that later on, when he could not deliver the initial start-up capital due to a lack of finances, he was removed from the signatory list. The letter from the Directorate of Registration of Businesses dated 20th December 2022 sets out that this company last produced accounting reports in 2019. See Annex 5.

Concerning South Gas Energy Company, Mr Arech explained that he had neither association nor knowledge of the existence of this company. The letter from the Directorate of Registration of Businesses dated 20th December 2022 sets out that this company did not exist in their database.

In relation to Alok Forex Bureau, upon registration of the company, both Mr Arech and his wife were invited to become shareholders, but they were both removed due to not delivering their start-up capital. This information was provided to The Sentry. The letter from the Directorate of Registration of Businesses dated 20th December 2022 sets out that this company has been dormant since 2012. The licence was revoked by the Central Bank of South Sudan in 2019 in accordance with their regulations.

Regarding his relationship with President Kiir and his position as his personal secretary, he explained in his communications with The Sentry that, by birth, the President is his maternal relative. He also explained that “Salva’s father’s grandmother is from our clan, so he calls me uncle.” When Salva Kiir became President, Mr Arech became his Personal Secretary and by virtue of this position, was automatically attached to the NSS. However, he resigned from the position on 11th October 2011, which is a matter of public record. These facts were ignored by The Sentry. He explained that he had never been trained, given any assignment in any NSS mission or an NSS salary.

While in America, Mr Arech got married, had a family and created a Non-Profit Organization called Jumpstart Sudan, the aim of which was to provide supplies of school materials, mosquito nets, blankets and medicines to Sudan, as it then was. He was an executive director but did not receive a salary.

Mr Arech concludes by stating that his reputation has been tarnished by the Report’s false allegations. He seeks a public retraction of the allegations, the conduct of additional verification research and an apology to him and his family.

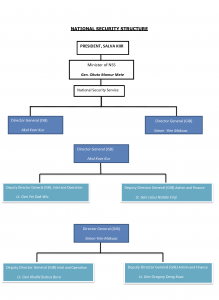

The Transitional Constitution of the Republic of South Sudan, 2011 pursuant to Articles 160 and 161 respectively established the NSS. The structure, mission, mandate, functions of the Service and the terms and conditions of the services of its personnel are prescribed in the National Security Service Act 2014. The NSS also has a parliamentary oversight mechanism called the Specialized Standing Committee on Defence, Security and Public Order. At Cabinet level, the NSS is represented by the Minister of National Security who also serves as a Member of the National Security Council (NSC) of South Sudan.

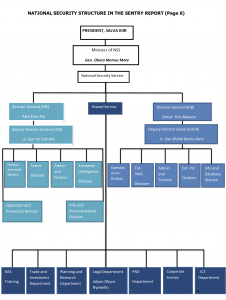

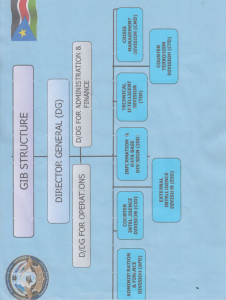

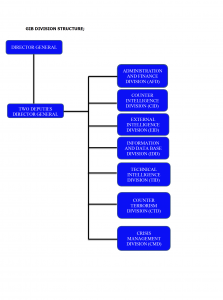

The organizational structure of the NSS relied upon by The Sentry is incorrect, out-of-date and does not reflect the current structure of the organisation. Neither does it represent “the structure of the NSS when it was constituted in 2013.” The diagram relied upon by The Sentry is no more than a proposed structure for the organisation in 2013, which was in fact not adopted. Inclusion of such a diagram demonstrates The Sentry’s disregard for insisting upon up-to-date information to demonstrate the present-day reality of the organisation. The correct organizational structure has been included in Annex 13. The Sentry failed to contact the NSS leadership including the oversight bodies prior to publication to verify the chart relied upon.

The Report makes generic and far-reaching allegations against the institution of the NSS based only on hearsay and information obtained from two unnamed individuals.

The hearsay sources consist of one media report,64 a generic one-page statement from the UN Secretary General on free press,65 a generic one-page statement from UN OHCHR on the importance of protecting civil space,66 a Human Rights Watch report67 and one paragraph from a report from the UN Panel of Experts, published nearly four years ago.68 The credibility of the two unnamed individuals cannot be probed given their anonymity.

i. Freezing of Assets

By way of example, one of the wide-ranging and erroneous allegations included in the Report is that “In July of 2021, the NSS instructed the Bank of South Sudan, the country’s central bank, to order commercial banks in South Sudan to freeze the assets and bank accounts of civil society members carrying out work that the NSS did not agree with.”69

Assets were in fact frozen by the Bank of South Sudan on 6th October 2021 and not by the NSS. Neither the correct context, nor the detail of the freezing of assets was included by The Sentry.

On 3rd August 2021, a criminal complaint was made before the Public Prosecution Authority of Northern Police Division by Daw El Bit Adam representing the South Sudan Police Service against seven named individuals, all of whom were members of a Non-Profit group established in 2018 in South Sudan called The People’s Coalition for Civil Action (PCCA). The basis of the complaint related to attempts by the individuals to inter alia subvert constitutional government and participate in gatherings with the intent to promote public violence and breaches of the peace, pursuant to sections 48,66,67,74,75 and 76 of the Penal Code 2008.

On 6th October 2021, a letter was written by the Director General of Banking Supervision, Research and Statistics (Bank of South Sudan) to all commercial banks operating in South Sudan with a directive to freeze and block the bank accounts of five of the seven suspects.

On 20th December 2021, the Senior Public Prosecution Attorney from within the Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs made an Order of Attachment of Accounts and Properties of the seven suspects. The document authorised and required the police and NSS to “seize and attach the movable and immovable Properties belonging to the said accused persons.”

Forensic evidence gathered during the investigation led to the State Legal Administration and Public Prosecution Attorney finding on 26th July 2022 that there was sufficient evidence to charge the individuals under sections 48, 52, 63, 66,67,74,76 and 80 of the Penal Code of South Sudan 2008, namely in respect of offences relating to subverting constitutional government, causing disaffection among police forces or defence forces, publication and communication of false statements prejudicial to South Sudan, undermining the authority of the President with knowledge of realizing that there is a real risk and possibility that statements were false and may endanger feelings of hostility or cause hatred, contempt or ridicule. The report concluded that charges must be brought against the individuals, a number of whom had since absconded and left South Sudan.

On 9th September 2022, a Special Court in Juba was established for the trial of those charged. The cases were ultimately dismissed for lack of evidence and six others absconded.

The Sentry’s erroneous allegations against the NSS betrays its lack of investigative rigour and displays its failure to set to out the correct information in respect of the legal process that was followed concerning the arrest, investigation, charge and freezing of assets of individuals within the PCCA. The relevant documents referred to above are attached in Annex 14.

ii. Deng Tong Kenjok

The Sentry also made an allegation within its section on “Crushing the Civil Society” that Deng Tong Kenjok, “the former registrar general of the governmental Relief and Rehabilitation Commission and an NSS agent…played a key role in pushing forward new and confusing policies on humanitarian activities and saw NGO fees raised in 2017.”70 Again, the sources relied upon for these allegations consist merely of a newspaper report explaining the Government’s decision to increase registration fees for aid agencies and one paragraph from a report of the UN Panel of Experts, published nearly four years ago.71

Deng Tong Kenjok is an officer from the Internal Security Bureau (ISB) and pursuant to the provisions of the National Security Service Act, officers and personnel from the NSS are deployed in various Government institutions to protect the National Security interests of the country. Deng Tong was deployed to the Relief and Rehabilitation Commission (RRC) before being assigned to a foreign posting.

The GoSS denies the allegation that Mr Kenjok played a “key role in pushing forward new and confusing policies”. In plain terms, Sudan’s NGO Act of 2003 was repealed and replaced with South Sudan’s NGO Act of 2016 which for the first time introduced the regulation of NGOs and civil society organizations, common in many countries.72 The NGO Act of 2016 was passed by the National Assembly in January 2016 and was signed into law by the President on 10th February 2016. Some donors, NGOs and civil society organisations resisted the introduction of regulation. None of these bodies were fined or deregistered. Mr Deng Tong Kenjok was the newly appointed regulator and Chief Registrar of the NGOs. The increase in registration fees for local NGOs was 50 US dollars, from $450 to $500, changes made due to the increasing demand of humanitarian needs in the country. The substantive allegations against Mr Kenjok are baseless.

The Sentry also alleges that “The NSS has taken the lead role in restricting the activities of anyone who is critical of the government, particularly journalists and civil society representatives, according to the report. These efforts are often led by Deng Tong Kenjok, an active NSS agent who ran the South Sudan Relief and Rehabilitation Commission”.

The one source relied upon for this substantial allegation is a two-page hearsay extract from a UN Panel of Experts report, issued almost 4 years ago in April 2019.73 This UN report relies on unnamed sources in interviews dating back to 2018 and 2019, none of which can be verified for either accuracy or potential bias.74 It is also unclear precisely how many interviewees formed the basis of the information and allegations contained in the 2019 UN Panel of Experts report. Mr Deng Tong Kenjok was not contacted or confronted with the allegations Sentry makes against him before publication.

The Report recommends the imposition of targeted network sanctions against inter alia Mr Jalpan Obyce, advising the US, UK, EU, Canada and Australia to urgently investigate and if appropriate, impose sanctions. 75

Alarmingly, the Report offers no evidence in support of its recommendation to have sanctions imposed against Mr Obyce. It merely posits that he has been a US citizen since at least 2012 when he was registered to vote and has owned property in Texas since 2003 both of which The Sentry alleges are “likely to provide [him] with access to the US financial system and subject [him] to US law.”76 No criminal behaviour or misconduct by Mr Obyce is alleged in the Report. The recommendation of the imposition of sanctions against Mr Obyce is irresponsible particularly given its potential impact on both the individual’s reputation and more widely, the stability of the country which is still struggling to recover from two attempted coups.

In his letter to The Sentry dated 10th February 2023, Mr Obyce began by correcting the Report’s organigram77 confirming “that there is no Shared Services Legal Department” as incorrectly alleged. As a “senior professional civil servant of the Republic of South Sudan, and a law-abiding citizen of the United States of America,” since 2005, he stated that “none” of the “allegations of corruption and human rights abuses” made against him in the report have “any foundation”. He explained that there is “a plain attempt by The Sentry to construct a false and misleading context to defame [his] character and reputation. The level of inaccuracy within the report is such that no bona fide human rights organization would issue such poorly researched and defamatory material unless they had an insincere motive to cause harm, distress and incite conflict.” Mr Obyce demands a “public letter of apology, a retraction of what has been alleged and a withdrawal of the Report.” See Annex 15.

No visit to South Sudan was conducted by The Sentry prior to publication of its report. Given the wide-ranging and grave nature of the allegations, it is of great concern that there has been no visit by The Sentry to seek to verify or corroborate the information obtained as part of its desk research on the ground in South Sudan.

The Report has no regard for the positive developments that are taking place within the NSS in South Sudan in respect of the establishment of NSS Tribunals, a complaints procedure, NSS reforms and detention centres. It is notable that no contact was made with the higher echelons of the NSS to investigate the current situation and to seek a direct response to the allegations made in the Report. An outline of these developments for the benefit of The Sentry is set out below.

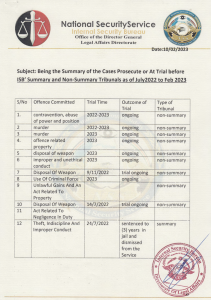

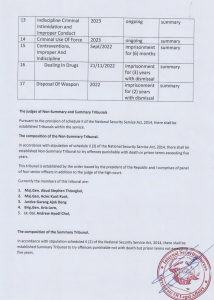

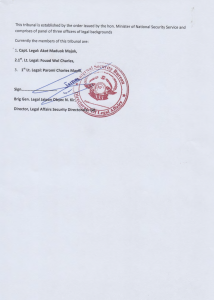

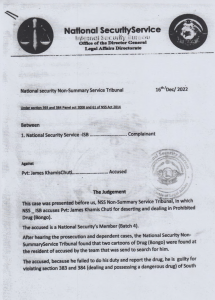

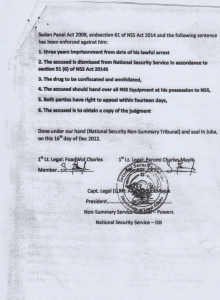

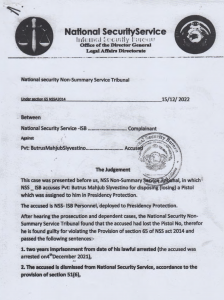

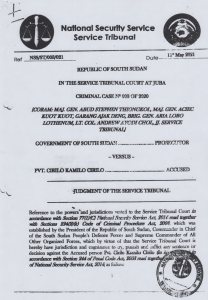

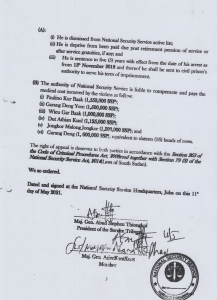

i. Establishment of NSS Tribunals

In December 2019, the NSS announced the establishment of two separate tribunals,78 namely a summary tribunal and a non-summary tribunal. The legal basis for their establishment is the National Security Service Act 2014.79 The tribunals have broad jurisdiction to try members of the NSS accused of criminal acts, disciplinary matters, breaches of the National Security Act 2014, and any other laws and regulations, including human rights violations.80 The composition of the tribunal is dependent on the seriousness of the offence. For the most serious offences that carry prison sentences of over 5 years (and for some that potentially carry the death penalty), the tribunal is composed of four officers and a High Court judge.81 The NSS tribunals are bound by the procedures laid down in South Sudan’s Code of Criminal Procedure.82

Despite only being recently established, from July 2022 to February 2023, the NSS’s Summary and Non-Summary Tribunals have held trials in relation to 17 distinct matters, some of which are ongoing.83 A table summarising the nature of these proceedings is attached at Annex 16. By way of example, two National Security Non-Summary Service Tribunal Judgements and a Judgement of the NSS Service Tribunal are attached in Annex 17.

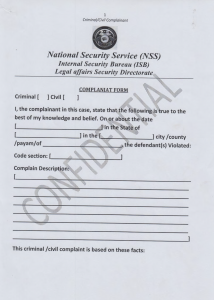

ii. NSS Complaints Procedure

The NSS Act 2014 provides for an internal accountability mechanism through the establishment of a Complaints Board.84 The complaints board can accept complaints about the procedural actions of the NSS from “any person” (this includes both the public and NSS agents).85

Members of the board are appointed by the President upon recommendation of the Judicial Service Commission.86 The Complaints Board has the same powers of the High Court to order production of relevant documents and summon witnesses.87 Hearings are held in private88 and where a complaint is upheld, recommended disciplinary action to be taken against the NSS member will be reported to the President or the Director General for final decision with the complainant informed in writing of the Board’s decision.89 An example of a Complaint Form is attached in Annex 18. In addition, there is also a Complaints Department within the Legal Department of the NSS.

iii. Reforms in NSS Recruitment and Training

The NSS has an established recruitment procedure.

The position of ‘Officer’ requires the attainment of a degree (a diploma is also considered acceptable). For the role of ‘Non-Commissioned Officer or other “personnel’ a certificate is required.91

All Officers and Non-commissioned Officers (NCOs) are expected to attend training at least once a year. In recent years, NSS officers (and non-commissioned officers) have attended joint training sessions conducted by UNMISS and the International Committee of the Red Cross (‘ICRC’) on international humanitarian law. Training programmes have also taken place with the Media Authority and national journalist unions on the legal limitations to freedom of expression.92

Specific training on conditions of detention centres and treatment of detainees has also been provided by the ICRC.93 This training included officers from the South Sudan National Police Service and Prison Services. Other training has included Officers and Non-Commissioned Officers from the Directorate of Legal Affairs on the Code of Criminal Procedures 2008.

There has also been joint training of officers and Non-Commissioned Officers from the National Security Service with those from the South Sudan National Police Service and the Prison Services (Correctional Centers) by the ICRC on how to manage detention cells and treat detainees. Detention cells and the welfare of detainees are checked daily to ensure acceptable conditions and that the rights of detainees are complied with.94

IX. NSS Detention Centres

The Response of the Revitalised Transitional Government of National Unity (“RTGoNU”) to the UN Panel of Experts Report (UNPOE Report)95 in 2020 challenges and rebuts the allegations of poor conditions at detention centres and the mistreatment of detainees by NSS officers. The allegations, that the UNPOE Report96 claim are ‘corroborated’ by other evidence, recycle earlier UNPOE reports using familiar (i.e. supportive) media sources97 that all follow a narrow and flawed narrative. In its Report, The Sentry relies on the recycling of information from the UNPOE, taking no regard for the information contained in the RTGoNU’s rebuttal of allegations.

Notwithstanding the inherent flaws in the UNPOE’s information as exemplified through basic factual errors98 and the failure to provide a reason for refusing the official invitation by the NSS to visit and inspect the Blue House and Riverside facilities,99 the NSS present in its response a contrasting picture of both facilities. Far from being notorious places of detention where detainees are abused,100 the Blue House and Riverside serve as the Internal Security Bureau (ISB) headquarters and offices. 101

The Sentry’s recycled information from the UNPOE provides an inaccurate structural layout of the detention facility at Riverside102 to substantiate its wide-reaching claims of poor living conditions, torture, killings and a culture of impunity. There is in fact only one holding cell which accounts for a tiny part of the modernised and fully renovated building. Riverside is located in a public area, next to a busy immigration service centre and water purification site managed by a foreign company.103 Soldiers reside there and conduct routine operations in Juba city.104 NSS officers who have committed criminal offences, soldiers awaiting court martial and other detainees are treated humanely and are visible roaming freely within the veranda area of the unit.105 This is not a secret location and its true image does not correspond with the description of the facility (and what allegedly takes place) within the UNPOE Report.

The Blue House, contrary to the allegations, has cells “fitted to modern standards of comfort and living. The cells are used exclusively for holding individuals awaiting trial. Detainees include suspects who pose a danger to national security and include members of the NSS suspected of criminal offences.”106 Regular family and legal visit rights are respected. The building is located within a residential area where NSS staff regularly interact socially with civilians on the adjacent football pitch outside the building.107 This contrasts with the nefarious reputation of NSS officers that The Sentry recycles from the UNPOE Report and other sources it relies upon.

In January 2019, NSS detained Brigadier General Malual Dhal Muorwel and 25 others at Riverside as a result of allegations of the unlawful detention, harassment and assault of a Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring and Verification Mechanism team.108 This related to an incident which took place on 18 December 2018 in Luri. However, the UNPOE in filing their report to the UN Security Council on 9 April 2019 failed to include the fact that Brigadier General Muorwel had been detained, charged and sentenced along with other officers for their conduct. The Sentry’s report issued in December 2022 recycles this misleading and incomplete information from the UNPOE without checking or providing the full facts as would be expected of a reliable research organisation.

Moreover, the ‘prison break’ by detainees held in the Blue House in October 2018 could easily have escalated into a violent and deadly confrontation but was peacefully resolved by the NSS through dialogue. Those involved in the prison break were not arbitrarily punished for their actions – they were prosecuted (publicly) in court with their rights observed. 109

X. Allegations of Illegal Detention

The Report section entitled ‘Illegal Detention’ is supported by four sources110 of which only a single source is relied on to support these allegations against the NSS. This single source is a Human Rights Watch report111 referred to extensively throughout the Report.112

In the absence of any of its own research, The Sentry attempts to frame the allegations (all of them taken entirely from the Human Rights Watch report) without further verification113 by claiming that the NSS does not conform with the UN Human Rights Council’s Guide on Good Practice for Intelligence Agencies (“the UN Guide”).114 In doing so, The Sentry selects a few random lines from this source.115 A closer look at this source shows however that these quotes are taken out of context. The Report claims that the powers to arrest and detain a suspect bestowed on the NSS by law are a “breach of international best practice.” 116 The Report refers to the UN Guide which it quotes as stating that intelligence services “are not given powers of arrest and detention if this duplicates powers held by law enforcement agencies117 that are mandated to address the same activities.” The actual text of the UN Guide makes it clear that intelligence agencies do not have powers of arrest and detention where “they do not have a mandate to perform law enforcement functions.” 118 This vital line was omitted by The Sentry and confirms that powers of arrest and detention are legitimate where an intelligence service has a legal mandate, which is the case in relation to the NSS.119 The UN Guide also acknowledges that “The functions of intelligence services differ from one country to another”.120 The allegation that the NSS’s authority to arrest and detain suspects is “a breach of international best practice” is incorrect and baseless.121

The Sentry also attacks the mandate of the NSS by suggesting that it has no, or insufficient, legislative oversight122 to ensure compliance “with international human rights standards on rights to liberty and fair trial, as well as the prohibition of torture and inhuman and degrading treatment”.123 In doing so, it fails to make any reference to the specific oversight protections contained in the National Security Service Act 2014.124

The Report makes generic allegations with no specificity or particularity in respect of the actual offences alleged by the NSS. It concludes simply by stating that “the NSS has been found to routinely make arbitrary arrests and detain people without access to legal counsel or a timely trial.” 125 Again, it offers no evidence, examination, verification (or even page reference) of the single source on which it bases these allegations (i.e. the Human Rights Watch report).126

The Report then moves on to the best practice guidelines on the operation of detention centres.127 It accuses the NSS of operating its own, unlawful detention centres where “detainees are often held without trial for a prolonged period with limited access to food, clean water, medical care, or communication with the outside world” and subjected to “human rights abuses committed by the NSS”.128 While it is accepted that some detainees charged with offences relating to national security are held pending trial at the Blue House and Riverside buildings, neither are designated detention centres. The Blue House and Riverside serve as the Internal Security Bureau (ISB) headquarters and offices. Further information is provided in the section above on Detention. While both contain a small number of cells for holding detainees prior to trial, these are fitted to modern standards of comfort and living with human and fair trial rights of detainees respected. Moreover, the allegations of poor detention conditions, abuse of detainees and violation of fair trial rights are lifted directly from the Human Rights Watch report. These allegations are simply a repetition of others’ work and a blanket delegation of responsibility to conduct its own research to challenge and/or verify serious allegations.

XI. Allegations of Silencing the Opposition

In the section ‘Silencing the Opposition’, The Sentry alleges that “the NSS is frequently used to arrest and detain political opponents and dissidents for no more than expressing an opinion or their political affiliations.”129 The Report cites several individuals, observations in respect of which are set out below.

The Sentry’s allegation of silencing the opposition takes no account of the fact that the Revitalised Transitional Government of National Unity (‘R-TGoNU’), formed on 22 February 2020 following the signing of the Revitalised Agreement on Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan (‘R-ARCSS’) on 18 September 2018 is a power-sharing government formed with former rebels which expressly incorporates opposition and dissident views within its ministries. This Revitalised Transitional Government was formed following two attempted coups in 2013 and 2016. The R-TGoNU consists of twenty ministers nominated by President Kiir, nine ministers nominated by SPLM-IO’s Riek Machar, three ministers nominated by the South Sudan Opposition Alliance (SSOA), two ministers nominated by Former Detainees and one nominated by other opposition political parties.

In respect of the specific allegations, this response provides context to the incomplete and inaccurate information published by The Sentry and makes no concessions as to the allegations against the NSS.

The Report refers to James Gatdet Dak, a south Sudanese journalist and former spokesperson to Dr Riek Machar Teny. During the second attempted coup in 2016, Mr Gatdet Dak wrote a Facebook post that caused incitement to violence and a rapid deterioration of the situation, leading to a shootout at the Presidential Palace and an attack by Riek Machar’s bodyguards on the Republican Guard. These details are not set out in The Sentry’s Report. Mr Gatdet Dak was detained and taken to court but was later released pursuant to a Presidential pardon after the signing of the Revitalized Peace Agreement in 2018.

The Report also refers to Kuel Aguer Kuel alleging incorrectly that he is still detained in South Sudan. Mr Kuel is an academic and former Governor of Northern Bahr el Ghazal State. He was detained in relation to his involvement with the People’s Coalition for Civil Action (PCCA) where he was a signatory to a declaration calling for the resignation of both the President and the First Vice President. Mr Kuel and others were arrested and charged with subverting constitutional government and attempting to overthrow the government by unconstitutional means. After two months of trial, the case against him was withdrawn for lack of evidence. He was cleared of all charges in December 2022 and continues to live in South Sudan. For more information, see the ‘Freezing of Assets’ section above.

In respect of Kanybil Noon, he is a representative of civil society organizations on the Strategic Defence and Security Review Board (‘SDSR’) of the RTGoNU from Tonj, Warrap State. He was charged with defamation in 2019 in respect of articles he wrote about General Akol Koor Kuc, the Director General of the Internal Security Bureau (‘ISB’), of the NSS. The civil case against him was later withdrawn following discussions between his family members and General Akol Koor Kuc.

Concerning Michael Wetnhailic, he is a South Sudanese Social Media activist from Tonj, Warrap state, and often addresses local leadership issues. Most recently, his posts have been directed against the work of the Director General of the Internal Security Bureau, General Akol Koor Kuc. He lives in Juba.

Joseph Bangasi Bakosoro is a South Sudanese politician from Yambio, Western Equatoria state. He is the current National Minister of public service and served as governor of Western Equatoria from 26 May 2010 until August 2015, at which point he was arrested by security officials on suspicion of mobilisation on behalf of the SPLM-IO. He was later released in early 2016 and pardoned by the President. He re-joined the SPLM on 15 July 2021 and is currently the Minister of Public Service of the Republic of South Sudan.

In respect of Samuel Dong Luak and Aggrey Idri, referred to in The Sentry Report,130 both men disappeared in the Republic of Kenya. The Republic of South Sudan has no information as to their whereabouts or how they disappeared. The Sentry’s allegations that the ‘ISB reportedly worked with the Kenyan intelligence service to kidnap’ them are denied.

Taking yet another example of inaccuracy, The Sentry incorrectly states that “as early as 2013, the agency [of the NSS] was expanded in response to concerns that the then-army Chief of Staff General Paul Malong, with whom Kiir and Kuc have had a long-running political rivalry, was becoming a threat to Kiir’s power. Although Malong is no longer army chief of staff, he still holds significant influence, having command of rebel forces.”131 Such a statement reveals The Sentry’s lack of knowledge of recent historical facts. Up until May 2017, General Malong worked alongside the Government and was the Governor of Northern Bahr et Ghazal state until April 2014. In its Report, the Sentry appears to be espousing the cause of an individual, Paul Malong, who continues to be engaged in armed conflict.

The failings of this Report reveal a serious lack of investigative rigour and misjudgement by making serious allegations of wrongdoing on the basis of misleading and false information. The Sentry has failed to properly apply the laws of South Sudan in respect of dormant companies and makes allegations of corruption with no evidence in support. The anonymous authors have even failed to grasp that even if individuals have shareholdings in start-up companies, it does not mean that those companies have engaged in any trading activity. A significant number of individuals have issued letters of complaint direct to The Sentry, providing corrective information. These letters, many of which threaten legal action, are appended to this response.

The only reasonable conclusion to be drawn from the substantial number of inaccuracies is that the report is an exercise in confirmation bias.

In respect of the recommendation of sanctions, international policies and strategies are being devised from sources that are not capable of being carefully scrutinised to establish the truth of their assertions. The knock-on effect is an undermining of attempts by the Government of South Sudan to establish law, peace and development in its own territory. This type of report is capable of causing unfounded distrust in government agencies and stoking conflict adding to the problems of a government having to deal with factions seeking to undermine it. Organisations such as The Sentry that seek to rely upon very narrow sources to justify its far- reaching conclusions without examination or disclosure of the bias of their source are dangerous provocateurs in a society attempting to be at peace.

The GoSS calls on The Sentry to withdraw “Undercover Activities” from circulation and to issue corrective statements and public apologies in relation to the individuals and companies referred to herein.

Annex 1

MOJCA public statement dated 4th January 2023

Annex 2

Letter from Mr Bernard Amour Makeny, the Managing Director of NILEPET dated 11th February 2023

Annex 3

Two letters from Manasa Machar Bol’s lawyers Kogweno and Bubi to The Sentry dated 14th and 24th November 2022

Annex 4

Statement/Letter from Ter Tongyik Majok to The Sentry

Annex 5

Directorate of Registration of Businesses’ letter dated 20th December 2022

Directorate of Registration of Businesses response to False Allegations in Sentry Report about Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs dated 22nd December 2022

Annex 6

Statement/Letter from Deng Malual Leek to The Sentry dated 9th January 2023

Annex 7

Statement/Letter from Kuac Atuer Wieu to The Sentry dated 17th December 2022

Annex 8

Statement/Letter from Emmanuel Akol Ayii Madut dated 6th December 2022

Letter from Dier Tong Ngor, Governor of the Bank of South Sudan to Chairman of Board of Directors of Alok Forex Bureau, dated 4th February 2019

Annex 9

Statement/Letter from Napoleon Adok Gai to The Sentry dated 6th January 2023

Annex 10

Letter from Professor Moses Macar Kacuol dated 4th January 2023

Annex 11

Statement/Letter from Jubek John Noel to The Sentry dated 10th January 2023

Annex 12

Statement sent to The Sentry dated 9th January 2023 from Miss Anne Rutere’s lawyers

Annex 13

Incorrect NSS Structure Used in The Sentry Report

Correct Official Structure of NSS

Correct Sentry-Style Structure of NSS

Annex 14

Letter from Moses Makur Deng, Director General of Bank of South Sudan dated 6th October 2021 to All Commercial Banks Operating in South Sudan

Order of Attachment of Accounts and Properties of the Following Accused Person (See Section 98 Code of Criminal Procedure Act, 2008), dated 20th December 2021

Report of the State Legal Administration and Public Prosecution Attorney on the Outcome of Investigation into a Criminal Case No 3980 Under Sections 48/66/67/74/76 and 80 of Penal Code, 2008 Opened Against Accused Kuel Aguer and Others

Establishment of Special Court in Juba for the trial of suspects/accused persons Kuel Aguer and others [FIR No.3980/2022] and Abraham Chol and Others [FIR No. 3536/2022] dated 9th September 2022 80

Annex 15

Letter/Statement from Jalpan Obyce to The Sentry dated 10th February 2023

Annex 16

Table summarising Cases Before ISB’s Summary and Non-Summary Tribunals from July 2022-February 2023

Annex 17

Two National Security Non-Summary Service Tribunal Judgements and a Judgement of the NSS Service Tribunal

Annex 18

Example of a Complaint Form re NSS Complaints Procedure

Annex 19

Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation of the Republic of South Sudan, Response of the RTGoNU to the UNPOE re (S2020/342) and (S2019/301) dated 27th May 2020

Introduction

Recent Complaints Against The Sentry

Methodological Flaws

Misleading and False Allegations of State Capture by NSS Shareholdings in a “Vast Network of Companies”

Incorrect Organizational Structure of the NSS

Insufficient Evidential Basis for Far-Reaching Allegations of NSS Crushing Civil Society

No Substantive Underpinning for the Imposition of Sanctions

No Visit to South Sudan to Investigate the Allegations Before Publication

No Regard for the Positive Developments Within the NSS

Inaccurate Allegations of Political Instrumentalization

Conclusion

Annex