Setting the record straight

Return Home

Return Home

Forces ready for transport to the training centres in Akoba County, Jonglei State. Republic of South Sudan

Chapter 1

This Chapter examines the impact and legacy of the failed 2013 and 2016 coup attempts in South Sudan and international involvement in the peace negotiations, against a backdrop of denials that coup attempts took place.1 By not acknowledging the reason for the conflicts, the basis and strategies of the subsequent peace agreements were inherently flawed. The agreements resulted in many concessions being required of the Government of President Salva Kiir Mayardit favouring actors who had set out on a violent armed path to take power. Building stable government institutions following these agreements has inevitably proved fraught with difficulties.

The misrepresentation of these conflicts by the international community has had damaging consequences for South Sudan’s economic development that has been further restricted by the imposition of sanctions and an arms embargo.2

Chapter 2

The history of Sudan leading to the creation of the state of South Sudan is mired in conflicts, coups, division, instability and political factionalism. Identity politics, ethnic and tribal affiliations and control of resources are framed as key factors for the conflicts.3 State armies, former rebel movements, militias and armed regional groups have all featured in ongoing conflicts for over seventy years.4 External actors have also used militias for their own proxy wars, resource gains, and/or power consolidation. It is also important to recognise the clear roles played by outsiders and their legacy in South Sudan today.

This Chapter examines the history of division and those armed groups that continue to influence South Sudan’s development. It also explains in part the complexities faced by the state to bring order and security to its lands.

Chapter 3

The prevailing way of life in South Sudan is traditional agriculture involving the raising of livestock. This way of life has led to acute competition and violent conflict over natural resources, such as water, fishing and grazing, among the various communities. Cattle are an important index of wealth and cattle raiding has long been rife among the ethnic groups, accompanied by violence and the abduction of women and children. These clashes have become more violent and deadly as traditional weapons have been replaced with modern hardware including rocket-propelled grenades and machine guns.5 Since its independence in 2011, scores of civilian armed groups have been identified as active across South Sudan. Splinter and sub-proxy groups continue to emerge. The state has had difficulty in controlling this violence while external actors have perpetuated a conflict narrative focusing on ethnicity rather than seeking to engage with the historical legacy of the country and the deep-seated grievances.6

This chapter identifies the core groups who continue to operate in violent hotspots, predominantly across the Upper Nile State and Jonglei State and provides the necessary context as to why these groups continue to thrive. On 31 December 2022, President Salva Kiir appealed to the South Sudanese parties to desist from violence and made a direct appeal deploring the violence7 in Upper Nile region and stating they could not stop it alone.8

Chapter 4

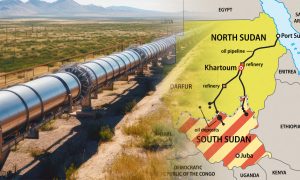

This Chapter examines South Sudan’s oil sector and the challenges it has faced since independence in developing its economic potential. South Sudan has a unique geographic position and the area is rich in hydrocarbons and offers enormous potential as a hub for the region’s petroleum services and exploration industry. The successful management and development of crude oil is crucial for the economic development and sustainability of the country.9 However, owing to the lack of domestic oil refining capacity, South Sudan has to export oil at fixed cost through the pipeline that runs from its oilfields through Sudan to the Red Sea.10 The terms of the Transitional Fee Arrangement (TFA) with Sudan for use of the pipeline to Port Sudan did not change in line with the reduction in global oil prices.11 South Sudan was bound by a fixed cost use of the pipeline meaning that a disproportionately larger share of the crude oil earnings were paid to Sudan.12

The oil industry is further hindered by poor infrastructure, conflict in oil producing areas, lack of investment and restrictive measures imposed by the U.S.’s Office of Foreign Assets Control and the Bureau of Industry and Security.13 In January 2012, the GoSS shut down its entire oil production in disagreement with Sudan over the transit fees it was required to pay for the use of the pipeline to Port Sudan amid allegations that Sudan had diverted oil.14 The pipeline remained closed for approximately 14 months and the dispute had a devastating impact on the domestic economy as oil revenues ceased.15 When the two attempted coups ignited the conflict in the oil producing regions, production was also interrupted.

Chapter 5

This Chapter examines the significant challenges overcome by the GoSS in achieving the unification of forces and the graduation of the first batch of the NUF under Chapter 2 of the R-ARCSS. It assesses the challenges posed by incorporation of the SPLM/A-IO (predominantly made up of militia elements) and other non-government aligned troops since 2018 and the real reasons behind key defections from the SPLM/A-IO. The difficulties of the unification process were underestimated with unrealistic timelines imposed. The unification of forces, previously in conflict, led to attempts by the SPLM/A-IO to unjustifiably skew the figures in the balance of troops to be numerically equal with the government forces.

Chapter 6

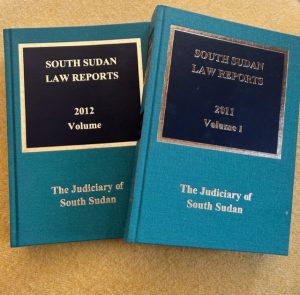

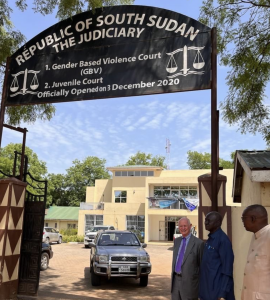

Shortly after gaining independence in 2011 many challenges to the development of South Sudan’s justice system were forecast by the Minister of Justice, John Luk Jok, who conveyed his firm intention to uphold the rule of law despite ongoing conflict. South Sudan had to transition from an Arabic language sharia-based law system to a pluralist legal system built on the combination of statutory and customary laws and courts. This significant shift in legal systems has impacted the speed at which the country has been able to rebuild its justice sector. Many court proceedings and judgments still use the Arabic language, even though South Sudan adopted English as its official language,16 and common law as its legal system.17

This chapter provides a unique insight into significant developments which have taken place within South Sudan’s justice sector since independence, noting the wide-ranging extent of the government’s cooperation with UN bodies to bring about change and the challenges it continues to face. Targeted international support which meets the particular needs of the country will be required in the years ahead in order to cement the progress that has been made.

Steven Kay KC with Justice Kulang Jarbong, Justice of the Court of Appeal, Mobile Courts in Juba

After the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005 (“CPA”), the then semi-autonomous region of southern Sudan made several significant achievements including the establishment of the essential institutions of government at the central, state and local government level, culminating in a successful, transparent referendum on independence in January 2011.18

One of the least developed countries in the world at the time of its independence,19 South Sudan set out to build a country almost from scratch, creating economic and governance institutions with a view to establishing an environment conducive to growth, peace and stability.20 The CPA marked an indelible turning point. The agreement declared “there shall be a national government” with full rights to exercise those functions and pass laws that “must necessarily be exercised by a sovereign state”.21 The CPA articulated the general structure of the government, calling for the creation of legislative, executive and judicial branches, and for the writing of an interim constitution. The International Monetary Fund remarked, “South Sudan’s challenges are formidable […] [m]uch has been done since 2005 and achieving independence on July 9 [2011] […] was a very important step, but the South Sudanese still have a long road ahead of them”.22

The challenges faced by South Sudan in 2011 were multidimensional, and complex. Among the myriad of demands, the Government would be responsible for preserving a fragile peace and building a functional government charged with providing a basic acceptable level of security and services for its people. A 2013 working paper from the Centre for International Development at Harvard University laid bare the challenges faced by the Government, stating that “[b]asically there is not a single government office in South Sudan that does not face critical capacity gaps – from the President’s office to the local administrators”.23

Since 2005, there has been an attempt to address the ‘capacity gap’ by the international community through significant levels of donor aid which to date has failed to fully engage with complex political and implementation issues. A meeting in December 2022 between the GoSS and UN Agencies in South Sudan underscored this point showing that the level of technical assistance and capacity building received thus far, did not reflect, or meet, the needs of Government institutions.24 This has long been the case and is part of a misunderstanding and failure to acknowledge the political realities caused by the two attempted coups.

Instead of long-term investment, donors have preferred to invest in short-term projects such as “random conferences and dialogues” that have struggled to deliver longer-term initiatives.25 UNMISS’s three-year strategic vision for South Sudan was only set out on 12 March 2021.26 Effective assistance and capacity building has fallen far short of the expectations of all sides.

Consequently, there are huge gaps in South Sudan’s institutional capacity, despite a large presence of international aid and development organisations operating across the country. These gaps are relied upon to criticise the GoSS for its “unwillingness” to build institutional capacity of its own.27 The Government has acknowledged capacity gaps and requested assistance in certain areas; namely calling for Item 10 Technical Assistance and Capacity Building each year at the UN Human Rights Council meetings in Geneva.28

The flawed approach to South Sudan can be traced back to the handling of peace negotiations by the international community following the attempted coup of December 2013. The rejection of the President’s statements of an attempted coup became the basis for the imposition of sanctions on key members of the GoSS along with an arms embargo, as the cause of the conflict was characterised as an ethnic attack, which it never was. Thereafter, the nascent Government’s inability to restore a lasting peace paved the way for a multitude of international institutions and governments to ‘take control’ of the situation by orchestrating negotiations between the GoSS and SPLM/A-IO and ultimately in 2015, imposing a peace agreement based on a flawed understanding and biased narrative. When that failed, the ‘revitalised’ Peace Agreement in 2018 has ensured continued international intervention ever since.

Grays Inn, London

This report is by a team at 9BR Chambers, who have worked with me on the international political and legal challenges the Government of South Sudan faces and seeks to set the record straight on some of them. The report should be read in conjunction with an earlier report we produced in 2022 titled: “Pushing the Reset Button for South Sudan”.29 The 9BR team are Gillian Higgins, John Traversi, Sarah Bafadhel, Lennart Poulsen, Doug Wotherspoon and includes our colleagues from outside Chambers, Ruby Sandhu and Jessica Lepehne.

Steven Kay KC

9BR Chambers

Gray’s Inn

London

September 2023

1.1 Introduction

This Chapter examines the impact and legacy of the failed 2013 and 2016 coup attempts in South Sudan and international involvement in the peace negotiations, against a backdrop of denials that coup attempts took place.30 By not acknowledging the reason for the conflicts, the basis and strategies of the subsequent peace agreements were inherently flawed. The agreements resulted in many concessions being required of the Government of President Salva Kiir Mayardit favouring actors who had set out on a violent armed path to take power. Building stable government institutions following these agreements has inevitably proved fraught with difficulties.

At the signing of the ARCSS in 2015, President Kiir warned that this was the “most divisive and unprecedented peace deal ever seen in the history of our country and the African continent at large” and that, “[t]his agreement ha[d] also attacked the sovereignty of [the] country”.31 These concerns were not heeded, and another attempted coup occurred soon after. Years of negotiations led to the R-ARCSS in 2018 and eventually the revised transitional Roadmap in August 2022.

From 2013 to the present day, the GoSS has operated against an insistent international narrative that focuses on ethnicity as the cause of the insecurity, rather than the attempted coups – a position reinforced by the release of the African Union Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan report in 2014 that also dismissed the coup allegations.32 This false narrative has, as a consequence, been used to support allegations against the GoSS of either failure to control violence or instigation of violence when SPLM/A-IO forces or related militia groups have in fact been responsible for insecurity across the country.33 These allegations have had a direct bearing on the nature and agenda of the negotiations that led to the prescribed peace agreement in 2015 and its revitalised successor in 2018 and thereafter. The failure to heed the concerns of President Kiir not only impacted the drafting of the peace negotiations but also caused significant delays in the implementation of the peace process which in turn has had a knock-on effect on the economy and prosperity of South Sudan. The resulting sanctions and arms embargo have restricted development in South Sudan, attempted to weaken the Government and led to an inherent mistrust of the international community’s motives.

1.2 Incorrect Assessment of December 2013 Attempted Coup

As set out in 9BR Chamber’s report ‘Pushing the Reset Button for South Sudan’,34 despite being informed on 16 December 2013 by President Salva Kiir that there was an attempted coup by forces of Riek Machar and his supporters, Special Representative of the UN Secretary General and Head of UNMISS Hilde Johnson,35 decided upon a policy to view the conflict as between two political sides.36 In her book, she referenced “targeted ethnic killings” and stated that “what clearly had been at first a fight between forces of the Presidential Guard loyal to the President and those siding with Riek Machar had degenerated into a deliberate massacre of Nuer, and particularly Nuer males”.37 Hilde Johnson later admitted in her book that what she knew on 17 December 2013, was “anecdotal at best”.38

Johnson explained that even though she had seen summaries of audio recordings of Taban Deng Gai organising troops and weapons supplies prior to the conflict, she questioned their authenticity and remained ‘unconvinced’ of a coup.39 Incorrectly, Johnson focused on politics and ethnicity as root causes and consequences of the violence, with her policy and assessment quickly setting the international agenda against the GoSS.40

On 24 December 2013 the UN Security Council issued Resolution 2132 “[d]etermining that the situation in South Sudan continues to constitute a threat to international peace and security in the region,” exercising its Chapter VII powers. In a subsequent press statement in January 2014, President Kiir questioned the role of the UN at the time stating, “I think the UN want to be the Government in South Sudan and they fell short of naming the chief of the UNMISS as the co-President of the Republic of South Sudan”.41

In an attempt to inform and prevent the ethnic conflict narrative from becoming the purported truth, UNMISS and the AUCISS were provided with summaries and audio material of telephone intercepts between Taban Deng Gai, military commanders, Riek Machar and other political leaders involved in planning and executing the attempted coup on 15 December 2013.42 This crucial evidence was not however taken into consideration and the ethnically driven narrative prevailed.

Nairobi, Kenya

1.3 Regional Responses to December 2013 Coup

In the aftermath of the December 2013 attempted coup, President Kiir reached out and declared his readiness to hold talks with Riek Machar and his supporters on 18 December 2013.43 Following this declaration, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development convened a summit in Nairobi on 27 December 2013 to set out a framework and parameters to guide peace negotiations. Despite repeated exhortations by IGAD and President Kiir himself, no representatives on behalf of Riek Machar or the opposition attended this summit.44 Unlike the UN the context of the conflict had been clearly understood by IGAD in its Communique of 27 December 2013 that condemned “all unconstitutional actions to challenge the constitutional order, democracy and the rule of law and in particular condemn[ed] changing the democratic government of the Republic of South Sudan through use of force”. IGAD, “welcomed the commitment by the Government of the Republic of South Sudan to an immediate cessation of hostilities and called upon Dr. Riek Machar and other parties to make similar commitments”.45

It is notable that in addition to IGAD, the attempted coup was acknowledged as such and condemned by several African countries – many of which had a thorough knowledge of the different political alignments in South Sudan and Riek Machar’s personal political ambitions.46 Even the U.S., while not explicitly acknowledging the coup, made a statement which included an indirect reference condemning the “effort to seize power through military force”.47

Gambia’s Secretary General and Head of the Civil Service and Minister of Presidential Affairs, Momodou Sabally, stated that the “attempted overthrow” of President Kiir’s government was unacceptable and that the protagonists of the attempt should desist from destabilising the country.48

Nigeria condemned what it defined as a “coup” and said that its “information further reveals that government forces were able to beat back the rebels. […] [d]estruction of property on a level yet to be determined has also been reported”.49

South Africa also identified the conflict as a coup attempt stating that “respect for democracy and human rights are essential to the governance of all African countries and that all violent means to overthrow legitimate governments must be rejected […] [i]t is therefore highly unfortunate that an attempt was allegedly made to undermine the stability of the country”.50

Ugandan President, Yoweri Museveni, similarly condemned what he referred to as a coup attempt and, according to a Reuters press release on 30 December 2013, claimed, “the nations of East Africa had agreed to move in to defeat South Sudanese rebel leader Riek Machar if he rejected a ceasefire offer”.51

Although a significant number of African states recognised what had occurred in December 2013, these countries had no control over the development of the international narrative that was about to unfold, which caused South Sudan to be locked into a never-ending cycle of international criticism, scrutiny, and interference.

1.4 A Flawed Western-Led Narrative Takes Hold and Sanctions are Threatened

The United Nations, African Union, the Troika, and the European Union preferred collective responses to the coup attempt of December 2013, narrating a political crisis that had escalated into ethnic violence carried out by the military and various armed groups.52 This account became the orthodox version of events and led the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, on 30 April 2013 to take the view that South Sudan was “on the verge of catastrophe” due to a “personal power struggle”.53

Following that statement, it was taken to another level by former U.S. Secretary of State, John Kerry, who warned of a possible “genocide” in South Sudan and raised the threat of sanctions. He stated that “[t]hose who are responsible for targeted killings based on ethnicity or nationality have to be brought to justice, and we are actively considering sanctions against those who commit human rights violations and obstruct humanitarian assistance”54 Kerry’s statement was made notwithstanding the position taken by UN Commissioner Adama Dieng the previous day that “[i]t is too early to determine whether recent violence in South Sudan amounted to genocide, but risk factors like hate speech and targeted killings based on ethnicity are causes for concern”.55

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

1.5 Agreement on Cessation of Hostilities January 2014 and its Subsequent Collapse

On 31 January 2014 in Addis Ababa, an IGAD summit was held to mark the Agreements on Cessation of Hostilities signed on 23 January 2014.56 Present at this meeting were Heads of State of the IGAD nations as well as representatives from the Troika, the United Nations and China.57 The summit noted with “appreciation” the eight-point roadmap outlined by President Salva Kiir “to wide consultations with all stakeholders…[in order to]… resolve the conflict in South Sudan in an all-inclusive manner”.58

On 18 February 2014, less than a month after the signing of the agreement, a South Sudanese Government official accused forces affiliated with the SPLM/A-IO of attacking Malakal, a key town in the Upper Nile. The fighting quickly spread across Upper Nile, Jonglei, Warrap and Unity States.59 IGAD’s statement on 19 February 2014 deplored the breach of the CoHA.60

After the collapse of the CoHA, IGAD with the support of the Troika, sought to develop a framework for peace. IGAD documents from March 2014 show both the GoSS and SPLM/A-IO broadly accepting seven thematic areas within a Framework for Political Dialogue.61 The Government proposed a phased approach focused on humanitarian access, negotiating a permanent ceasefire and national political conference to discuss governance, constitutional and institutional reforms; whereas the SPLM/A-IO viewed the Framework as a working document and proposed changes calling for a complete overhaul of institutions of governance.62 This suited their agenda and afforded them a level of international legitimacy which would thereafter shape the future of South Sudan when President Kiir and Riek Machar convened in Addis Ababa on 9 May 2014 and signed the ARCSS.63 A Transitional Government was outlined as the best chance for the people of South Sudan to take the country forward. The U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, described it as the “breakthrough” to stop fighting and to negotiate a transitional government.64 On 2 May 2014, Kerry had issued a statement following his meeting with President Kiir noting the need for a transitional government to bring peace to the country and recognising the position of the “sitting president, constitutionally elected and duly elected by the people of the country and a rebel force that is engaged in [the] use of arms in order to seek political power or to provide a transition”.65

1.6 Government Concessions to SPLM/A-IO

Since December 2013, peace talks have been externally led and sanctions imposed on key members of the GoSS’ negotiation team raising objections or proposing changes on the basis that they were “obstructing the implementation” of the ARCSS.66 The fairness of such tactics to force terms is questionable. From December 2013, continued criticism and pressure by the international community of the GoSS benefited Riek Machar and his supporters, allowing them to stall peace talks in the hope that the Government would collapse, in a bid to enable Riek Machar to fulfil his self-proclaimed ambition of becoming president.67 In 2018, one commentator expressed his view in the following terms: “[t]he government is increasingly convinced that the Troika68 and UN are undermining efforts to reach peace, and emboldening Riek to not make compromise. This was demonstrated by a choreographed release of the UN report of alleged atrocities committed by the government forces against civilians in Unity state. The report did not blame the rebels”.69

During the peace negotiations, the GoSS made several notable concessions including President Kiir’s ordering a stay of criminal charges and releasing the suspects charged with the attempted 15 December 2013 coup. This concession had a tangible effect and contributed to the conclusion of the ARCSS on 9 May 2014.70

Nhial Deng Nhial, the GoSS chief negotiator during the peace talks, emphasised other concessions made by the Government, as contributing to a “breakthrough”.71 These included President Kiir’s concession that Riek Machar would be able to run for the position of Prime Minister under the Protocol on Principles on Transitional Arrangements.72

At the IGAD summit in Addis Ababa on 10 June 2014, President Kiir and the GoSS were commended for “releasing all the political detainees” as well as “their engagement in the negotiation process”.73 Paradoxically in the same communique, IGAD simultaneously expressed its disappointment in what it considered failures of both the Government and the SPLM/A-IO to engage in the peace process meaningfully.74 Such contradictions in the tone and approach of IGAD diluted the positive actions and progress made by the GoSS. Riek Machar and the SPLM/A-IO, for their part, had not offered any meaningful concessions to further the peace negotiations.

1.7 The Arusha Agreement – A Missed Opportunity for Peace?

In the spring of 2014, an alternative mediation initiative was established, designed to pursue a settlement by reconciling the SPLM at a distance from the influences of the international community.75 The parties converged in Arusha, Tanzania, to discuss unification at the party level as a way of resolving the conflict and signed what is now known as the “Arusha Agreement”. This Agreement provided for a return of all political leaders to the SPLM, where they would discuss democratisation to rectify national problems. All members would be reinstated in their previous positions and would be eligible to contest elections. SPLM Secretary General, Pagan Amum, returned to Juba to a warm welcome with the aim of reuniting and reorganising the party. However, the Troika countries’ negative attitude towards a non-Western led peace agreement was evident as reflected in a comment made by one Troika diplomat, stating “[w]hy do you want to resurrect a dead monster”.76

Arusha city, Tanzania

The Troika countries came up with a new proposal, presented by IGAD, to circumvent the ideals of Arusha.77 The proposal created the position of the First Vice President, to be filled by Riek Machar and it is alleged that upon “seeing this, Dr. Riek jumped onto the proposal and abandoned Arusha”. This marked the end of the Arusha Agreement and with it, an opportunity for peace. It also set a precedent for a form of government that was totally unworkable and revealed a western bias favouring Riek Machar, one which he set to exploit.

1.8 Calls for “Actions not Sanctions” – Spring 2014

On 3 April 2014, the Office of Foreign Assets Control of the U.S. Department of the Treasury implemented the South Sudan sanctions regime following Executive Order 13664.78 Grounds for implementation were based on the preceding widespread violence and atrocities, human rights abuses, recruitment and use of child soldiers, attacks on peacekeepers and the obstruction of humanitarian operations.

On 2 May 2014, South Sudan’s former Minister of Foreign Affairs gave an interview in which he gave a commitment to investigate all cases of human rights abuses and hold people to account. He reiterated the importance of bilateral relations between South Sudan and the U.S., the need for goodwill and assistance to be provided to South Sudan to build security, strengthen the capacity of the police and the new army and that “what South Sudan needs is help and assistance – not punishment or conditionalities”.79

In spite of calls from a number of United National Security Council members resisting the imposition of further measures and calls for “Actions not Sanctions”,80 additional UN sanctions were later imposed from 2015 onwards, including a UN arms embargo,81 EU sanctions82 and a UK financial sanctions regime.83

1.9 Attempts at Power Sharing with Rebels – Summer 2014

By 10 June 2014, both President Salva Kiir and Riek Machar agreed that within sixty days, dialogue on the terms of a Transitional Government of National Unity would be achieved, providing the “best chance for the people of South Sudan to take the country forward”.84

On 20 June 2014, at the rescheduled launch of the Multi-Stakeholder negotiations for South Sudan, the Government of President Kiir and the SPLM/A-IO were congratulated for demonstrating the courage to commit to an inclusive peace process. However, the SPLM/A-IO boycotted the process, demanding involvement of only the “two warring parties” in the negotiations of all the issues in the IGAD Framework Agenda for the resolution of the crisis in South Sudan.85 The SPLM/A-IO stance led to the commencement of peace talks without them. The government delegation then stated it could not participate in further meetings in the absence of the SPLM/A-IO. This led to the adjournment of the process which had aimed to set out the transitional institutions and government as well as finalise the modalities for the implementation of the CoHA.

Talks resumed in August 2014 resulting in the 27th Extraordinary Summit of the IGAD Heads of State and Government endorsing the Protocol on Agreed Principles on Transitional Arrangements Towards Resolution of the Crisis in South Sudan.86 The Protocol was signed by President Kiir but not by Riek Machar. The Protocol called for the Head of State and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of TGoNU to be the elected incumbent President of the Republic who was to be deputised by a Vice President of the Republic. The office of Prime Minister would be established and nominated by the SPLM/A-IO. The Executive of the Transitional Government comprised the President, the Vice President, the Prime Minister and Council of Ministers. The Transitional Government was to include representatives nominated by the Government, the SPLM/A-IO, SPLM leaders and other Political Parties.87 This proposal88 was rejected by the SPLM/A-IO. Other stakeholders, namely the SPLM Leaders (Former Detainees), the Political Parties and representatives of Civil Society rejected other power sharing principles.89 On 22 September 2014, a revised draft was circulated by IGAD setting out how power was to be shared.90

The resolution of the precise arrangements for power sharing remained an ongoing issue that significantly delayed the signing and implementation of the peace agreements,91 as reflected in the Reservations of the GoSS on the Compromise Peace Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan, 26th August 2015.92 This substantive document, in which the GoSS noted its detailed reservations to the proposed peace agreement had been shown to international negotiators who had refused to acknowledge it.93 In the absence of comprehensive resolution of such matters of substance, it is unsurprising that the foundation of the resulting peace agreement was untenable.

1.10 Riek Machar uses the International Narrative – December 2014

In December 2014, Riek Machar gave a speech in Pagak at the start of the SPLM/A-IO conference in which he stated “[w]e are about to mark the first anniversary of the Juba genocide carried out by President Salva Kiir against his people killing over 20,000 innocent lives of Nuer people in less than a week. The massacres against Nuer in Juba triggered the present civil war, which Kiir feigned as a coup against the state. Our people and the whole world knew there was no coup”.94 A year earlier, he had described himself at the ‘scapegoat’ for the violence and denied the coup attempt.95

Following the December 2014 conference, Riek Machar set out lengthy resolutions in his ‘Search for Sustainable Peace and Good Governance in South Sudan’.96 He held President Salva Kiir directly responsible for an alleged Juba genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, stating that he had therefore lost his legitimacy.97 Regarding the cause of the conflicts, Machar claimed that President Kiir had launched a military campaign on 15 December 2013 with the objective of stifling democracy and eliminating his opponents in order to institute a totalitarian regime. Machar claimed that these actions plunged South Sudan into a civil war.98

9BR Chambers’ report ‘Pushing the Reset Button for South Sudan’ clearly shows this account to be a deliberate misrepresentation of events.99

1.11 July – August 2015: Concluding the ARCSS

As part of the peace process, in July 2015, U.S. President Barack Obama invited the leaders of IGAD to a summit in Addis Ababa. After the meeting, it was determined that the parties should finalise a negotiated settlement by 17 August 2015.

Concern arising from the adverse impact of the pressure to conform to the IGAD/Troika/UNMISS-led agreement was evident. On 10 August 2015, just one week before the deadline, Ugandan President Museveni proposed substantial changes to the draft agreement. This included alterations to the proposed power-sharing formula and, more consequentially, to its prescribed security arrangements. While this last-minute intervention was denounced by the international community and ultimately did not derail the eventual signing of the ARCSS, the concerns and alterations proposed by President Museveni were to be echoed by President Kiir during the signing ceremony.

On 17 August 2015, Riek Machar signed the ARCSS on behalf of the opposition, together with a representative of the SPLM former detainees. President Kiir decided not to sign the peace deal because in his view it threatened “to divide the country further”.100 It is noteworthy that even Riek Machar and his allies in the SPLM/A-IO expressed reservations about the agreement, though they declined to set these out publicly as it was more beneficial for them to increase their political standing (and avoid alienating the international community) by agreeing with it.101

The Troika, United Nations, IGAD and wider international community united to force through the ARCSS by giving President Kiir fifteen days to sign the agreement.102 This position put President Kiir and the GoSS under intense pressure, increased by the United States submitting a draft resolution to the UN Security Council calling for wider sanctions and an arms embargo if the ARCSS was not agreed by 1 September 2015.103 President Kiir considered that the power-sharing model would leave South Sudan without an effective and functional government. Working through IGAD, the international community increased this pressure by arranging to send Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, Sudan’s First Vice-President Bakri Hassan Salih and Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta to Juba.104

Confronted with international pressure, the threat of an arms embargo and targeted sanctions, President Kiir relented and signed the agreement at a ceremony in Juba on 26 August 2015.105 At the signing ceremony President Kiir outlined a number of substantive reservations about how the conduct of the mediation and about the ARCSS, including the viability of power-sharing which eroded the sitting government’s authority.106

President Kiir’s concerns were echoed by others, highlighting the fragility of the peace agreement and casting doubt over the prospects of long-term security and stability in South Sudan.107 The security arrangements provided for in the agreement during the transitional government period demanded that both government and opposition forces be redeployed outside a 25km radius around Juba. This meant that South Sudan effectively had two armies, with President Kiir in command of the South Sudan army and Riek Machar retaining control of his forces until the two could become unified – a process that would take several years. While the two militaries remained under separate command, the ceasefire would inevitably be compromised.108

President Kiir commented that the agreement “is the most divisive and unprecedented peace deal ever seen in the history of our country and the African continent at large […] [t]his agreement has also attacked the sovereignty of our country […] [t]here were many messages of intimidations and threats for me in the last few weeks, to just sign the Agreement silently without any changes or reservations […] [t]here is no doubt in my mind that the implementation of some of the provisions 109 of the Agreement will be confronted by practical difficulties that will make it inevitable to review or amend such provisions”. He added, “[w]ith all those reservations that we have, we will sign this [ARCSS] document […] some features of the document are not in the interest of just and lasting peace. We had only one of the two options, the option of an imposed peace or the option of a continued war”.110

President Kiir explained that Article 5.5 of ARCSS provided for a de facto demilitarisation of Juba, yet the “army has the responsibility to protect the nation, its people and leadership”, “which is a matter of sovereignty” and therefore should remain stationed in the capital. His stance was however misinterpreted and his references to the “failed coup” taken as a “signal that mistrust and suspicion will still characterise his working relationship with Machar in the TGoNU”.111 The complete denial by the international community that a coup had occurred served to undermine the GoSS, embolden the coup plotters and shift the power balance in favour of international actors to dictate the peace process.

Juba, South Sudan

1.12 Riek Machar: 2016 Coup Attempt, Exile and Return to Juba

The inherent lack of ownership by the parties of the ARCSS led to foreseeable problems with its implementation. Soon after signing the ARCSS, Riek Machar arrived in Juba with sophisticated weapons and troops in violation of the agreement.112 He also launched a charm offensive promoting peace, unity and solidarity with the government. On 8 May 2016, he called for “forgiveness and reconciliation in South Sudan”.113 On 22 May 2016, he attended prayers at a predominantly ethnic Dinka church telling the congregation “that peace and reconciliation will enable national healing and ensure stability”.114

However, the report “Pushing the Reset Button for South Sudan”,115 reveals the evidence from telephone intercepted communications that established the First Vice President was plotting a coup to seize power. Whilst he was presenting a unified front to the international community, in the background he was preparing forces of the SPLM/A-IO and using support from a foreign government, the Republic of Sudan, to provide arms and ammunition. On 8 July 2016, during his meeting with President Kiir and Second Vice President James Wanni Igga in the President’s office to resolve issues over the deaths of four government soldiers three days earlier,116 Riek Machar’s forces launched a second coup attempt in Juba. The conflict that took hold over the next few years resulted in great loss of life including the deaths of civilians.

Riek Machar never resumed the reconciliation talks that were taking place between the leaders of the TGoNU and was provided with safe havens outside South Sudan.117 The institutions of the United Nations having been bound by the narrative they had followed from the time of the first attempted coup in December 2013, continued with the same humanitarian agenda against the GoSS. This narrative remained locked in the prism that the conflicts were ethnically driven, and responsibility shared between the protagonists. While the GoSS reported the attempted coups to the UN Security Council, these reports were neither accepted nor referenced.118

The institutions of the United Nations did not recognise that the coup attempts were the result of the pursuit of an ambition that stoked and utilised ethnic divisions. They also failed to adequately recognise the rights of a sovereign state to control its territory and prevent unlawful and violent attempts to usurp the structures of power and government.

It is notable that Machar’s rumoured return to South Sudan (upon the insistence of the Troika) was met with opposition not only from the GoSS but from several IGAD countries. For instance, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn (who at the time was the sitting IGAD Chairperson) stated, “we will not support an armed struggling group or anyone who opts for the path of war and therefore we will not allow any armed movement which is detracting from peace in our region both in Ethiopia and South Sudan”.119 A separate diplomatic source was reported to have confirmed that the IGAD ‘peace negotiators’ were opposed to the return of Riek Machar because he “keeps going back and mobilising his people and stirring up problems”.120

While Riek Machar remained under an IGAD-imposed house arrest in South Africa,121 the SPLM/A-IO in Juba appointed lead negotiator Taban Deng Gai to replace him and the Government accepted him as acting Vice-President.122 Deng Gai fully defected to the Government in July 2016, and officially replaced Riek Machar as First Vice President. While IGAD eventually conceded that there was no choice but to accept Machar’s return if ARCSS was to succeed, it is revealing that the perception of Machar among many of those directly involved in the peace negotiations was negative. In March 2018, IGAD reluctantly decided to lift Riek Machar’s house arrest in South Africa but made it clear that this was “on conditions that ensure he will renounce violence and not obstruct the peace process”.123

1.13 Revitalised Peace Negotiations: 2016-2018

1.13.1 Establishment of the High-Level Revitalisation Forum (HLRF)

Even before the attempted coup in July 2016 and consequent conflict, IGAD had come under pressure from the EU and the Troika to revive the peace process.124 To this end, a framework to reconvene negotiations and drive the process of revitalisation of the ARCSS, known as the High-Level Revitalisation Forum was established in June 2017. This body consisted of seven countries from the region: Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, and Uganda.125 The HLRF brought the Government together with opposition leaders – some of whom formed new rebel groups, and opposition political parties who were hoping to benefit from any future power-sharing agreement.126 In 2017, Nikki Haley, then U.S. Ambassador to the UN, met with President Kiir and demanded he commit to the IGAD-launched HLRF.127

The mandate of the HLRF was threefold: first, to restore a permanent ceasefire; second, to fully implement the ARCSS; and third, to revise the ARCSS implementation schedule in order to hold elections at the conclusion of the agreement’s timetable.128 Staff from IGAD and the Joint Monitoring and Evaluating Commission were tasked by IGAD leaders to administer the HLRF;129 an indication that it was a repurposing of existing mechanisms, with no appreciation for the view espoused by the GoSS that key features of the 2015 peace agreement were no longer political or practical realities.

The U.S. Institute of Peace noted that “[w]hile the HLRF initiative demonstrates IGAD’s continued attention to the crisis in South Sudan, serious ambiguities, including the questions of who will participate and the extent of the agenda, exist in its design. If such uncertainties remain unaddressed prior to the commencement of the Forum, the prospects for this initiative to reduce violence and restore peace to South Sudan will be poor”.130 Those uncertainties were not addressed.

Although the HLRF’s mandate was to ensure “full implementation” of ARCSS, with just over a year until elections were due in August 2018, this requirement was unrealistic given the dire humanitarian and security crisis in South Sudan. Even if sufficient time for implementation were available, many of the ARCSS provisions of governance (Chapter I) and security arrangements (Chapter II) had been overtaken by events.131 Certain ARCSS provisions negotiated and drafted in 2014–15 also needed re-examination. For example, local ceasefires independent of the bilateral permanent ceasefire arrangements of ARCSS were subsequently necessary where third parties were involved. Such arrangements were not foreseen in the originally negotiated security protocols and could not be included without significant revisions to the text.132

1.13.2 Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS) Signed in September 2018

From 18-21 December 2017, the first HLRF summit was conducted in Addis Ababa which led to the Agreement on the Cessation of Hostilities, Protection of Civilians and Humanitarian Access, signed on 21 December 2017. Over the next few months, several meetings and discussions were held in Khartoum that resulted in several preliminary agreements that would set the stage for the Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan.133

Ethiopian Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed played a key role in negotiating the peace process and set up a meeting between President Kiir and Riek Machar in 2018. At this meeting, Machar insisted he be allowed to remain as First Vice President as advocated by John Kerry in 2014.134 President Kiir is reported to have stated that he would accept Riek Machar’s return as a private citizen but would not work with him again and requested the appointment of an alternative to the position of First Vice President. Riek Machar did not agree, and the meeting ended in a stalemate.

Sudan then took up the negotiating lead – despite its previous political and military support for Riek Machar.135 The potential lifting of U.S. sanctions against Sudan and proceeds from the oil revenues were motivating factors in the country’s rapprochement with South Sudan.136

By 2018, the situation in South Sudan was being referred to as a “bloody power struggle” between President Kiir and Riek Machar.137

The R-ARCSS was eventually signed on 12 September 2018 by nine political signatories and 16 civil society stakeholders.138 Its provisions are very similar to those of its predecessor: a permanent ceasefire; a power-sharing transitional government; followed by elections after three years. It also included the provision that “[t]he Chairman of SPLM/A-IO Dr Riek Machar Teny shall assume the position of the First Vice President of the Republic of South Sudan”. In addition, it had a more ambitious timeline for establishing a unified army, and included provisions to determine the country’s internal borders, which were the subject of considerable gerrymandering during the war.

Riek Machar returned to Juba in October 2018 following the signature of the R-ARCSS the previous month.

By March 2019 however, the ICG tellingly described the R-ARCSS as having established a “wobbly Kiir-Machar truce and graft[ed] onto the previous failed peace terms, without delivering much benefit to other groups that have been shut out of power”.139 Ultimately, Riek Machar was appointed First Vice-President of South Sudan on 22 February 2020 as part of the RTGoNU.140

14. Conclusion

The process leading up to the signing of the ARCSS in 2015 was characterised by significant pressure from the international community, underpinned by a lack of understanding, or acknowledgement that the attempted coup in 2013 was the reason for the ensuing conflict. Even as late as September 2014, when the GoSS set out the 42 milestones it had achieved to bring South Sudan to peace in a briefing to UNSC representatives in Juba, still the attempted coup was not acknowledged in UN reports.141 This misrepresentation of the conflict resulted in an initial peace deal that was fragile, flawed and susceptible to manipulation.

President Salva Kiir’s concerns and warnings went unheeded and another attempted coup in 2016 occurred soon after the signing of ARCSS. Years of negotiations ensued leading to the eventual signing of the R-ARCSS in September 2018. Ultimately however, both peace agreements imposed a framework for the Government of President Salva Kiir to share power with individuals who had led two attempted coups, a situation described as “Reward for Rebellion” which resulted in a legacy that continues to prevent South Sudan’s political, economic and social development.

2.1 Introduction

The history of Sudan leading to the creation of the state of South Sudan is mired in conflicts, coups, division, instability and political factionalism. Identity politics, ethnic and tribal affiliations and control of resources are framed as key factors for the conflicts.142 State armies, former rebel movements, militias and armed regional groups have all featured in ongoing conflicts for over seventy years.143 External actors have also used militias for their own proxy wars, resource gains, and/or power consolidation. It is also important to recognise the clear roles played by outsiders and their legacy in South Sudan today. This Chapter examines the history of division and those armed groups that continue to influence South Sudan’s development. It also explains in part the complexities faced by the state to bring order and security to its lands.

2.2 Colonialism

The colony of Equatoria was established in 1870, encompassing much of what is now South Sudan. It was made a state under the Anglo-Egyptian condominium in 1899 and largely left alone for decades. Colonial administrators ruled Equatoria separately from what is now known as Sudan. More powers were due to be conferred on the South following independence in 1956 but when the Arab-Khartoum government reneged on this promise soon after, a mutiny began in Torit,144 that would lead to two periods of conflict (1955 to 1972 and 1983 to 2005), during which millions were killed or died from starvation and drought.145

2.3 Independence

Britain’s decision to grant independence to Sudan was based on political expediency, not economic preparedness. It occurred before disparities in development could be addressed and without safeguarding the interests and representations of the southern Sudanese.146 Elections followed independence with Egyptian supported Ismail al-Azhari, leader of the National Unionist Party (NUP) winning against the British supported Ummah Party, headed by Sayyid Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi. Sudan was declared an independent republic with a representative parliament on 1 January 1956.

Sudan started its independence with a temporary constitution. Two issues arose which prevented agreement on a permanent constitution at this time: firstly, whether Sudan should be a federal or a unitary state and secondly, whether it should have an Islamic constitution.147 Southerners favoured federalism as a way of protecting southern interests. This was rejected by the North, who saw federalism as a first step to independence.

Despite the elections of 1957, General Ibrahim Abbud, Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces came to power in 1958 by military coup, bringing an end to civilian rule and electoral politics. Alliances then formed across the south with new generations of leaders emerging. General Abbud came to power criticising the mistakes of the preceding parliamentary government alongside the corruption, bitter political strife, and encouragement of foreign intervention.148

The new military government soon began to suppress opposition movements, which engendered a groundswell of resistance against military rule across Sudan, including in the south. Abbud followed an education policy of Arabisation and Islamisation in the south and had a deep mistrust towards the missionaries whom he believed were central to the separatist movement. Christian missionaries were eventually expelled in 1964, which only served to accelerate conversion to Christianity as churches were also seen to be under assault from the Government of Sudan.149

Initially, the government campaign against armed opposition in the south was limited but this increased in the late 1950s with an intensification of assaults against villages. This saw several senior figures, such as Catholic priest Fr. Saturnino Lohure, Joseph Oduho and William Deng as the leaders of the militant diaspora and other students, leave for the bush and form an exiled political movement and establish a core guerrilla army.150 The exile movement called itself the Sudan African Nationalist Union. The guerrillas became known colloquially by the vernacular name of a type of poison: Anyanya.151 The Anyanya became a rallying point for southern frustrations. The various Anyanya groups were scattered across the bush and, although they communicated through messengers, operated autonomously and mainly in small hit and run operations and acts of sabotage.152

2.4 First Civil War: 1963-1972

The reneging of the Khartoum based, Arab-led, Sudanese government on promises to create a federal system for the south led to the first civil war, from 1963 to 1972, as the Anyanya began their fight against Sudan for greater autonomy.

By 1969, the Anyanya controlled most of southern Sudan but the Anyanya groups were relatively autonomous and not unified. There were also competing tensions between the South, Khartoum and the diaspora. New political leaders emerged but most politically active Southerners organised under SANU. There were several attempts to unite the Anyanya but these were unsuccessful. The diaspora also remained fragmented with competing governments in exile proclaimed.153 External patronage proved essential for the southern guerrilla movement as it was supported by a steady supply of arms and weapons. In return, exiled leaders garnered for themselves much needed support, influence and leverage over the Anyanya groups.

2.5 Mohammed Nimeiri and Joseph Lagu

General Abbud stepped down in 1964 as Sudan’s economy was failing badly and demonstrations against his rule increased. Civilian rule was returned temporarily but in May 1969, a group of young officers led by Colonel Jaafar Mohammed Nimeiri came to power in Sudan in a coup described as the ‘May Revolution’, promising that everything must change. By this time, there was no workable constitution, a stagnant economy, a political system torn by sectarian interests and a continuing civil conflict in the south. Nimeiri was seen as popular in the South and “a man who guarantees a fair deal for the region” but this was double sided as his policy towards the south was a way to consolidate his political power in the north through his alliances in the south.154

Colonel Joseph Lagu was formerly Eastern Commander of the Anyanya armed forces and would eventually unite all the Anyanya officers under his command, including the political wing, Southern Sudan Liberation Movement, declaring the Anyanya as sole authority in southern Sudan.155 With the help of Israeli arms, advice and assistance, Joseph Lagu had persuaded a number of Anyanya to join him throughout 1970 and engineered a series of internal coups leaving the old, exiled southern politicians with no military constituency.156 In January 1971 he formed the Southern Sudan Liberation Front (later renamed the Southern Sudan Liberation Movement and the precursor to today’s Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army) under his command. This unified command, with a secure supply of weapons ensured the political wing was subordinate to the military branch.

2.6 Addis Ababa Agreement 1972

In 1971, Nimeiri entered dialogue with Colonel Lagu regarding regional autonomy and the ending of hostilities with southern Sudanese rebels. Enthusiasm for negotiating with Sudan was not shared across the rejuvenated Anyanya army. Dialogue between Nimeiri and Lagu, however, culminated in the signing of the Addis Ababa Agreement in February 1972, with the SSLM seen as an equal negotiating partner. The Addis Ababa Agreement granted significant regional autonomy to southern Sudan on internal issues, leading to far better conditions than had been previously seen.

The Addis Ababa Agreement brought Nimeiri both prestige abroad and popularity at home as well as with the SSLM. The Agreement was an historic occurrence in post-colonial Africa for the successful resolution of an internal conflict. However, the triumph was short lived as many were disappointed that the goal of independence had been abandoned and the unravelling of the Agreement began almost immediately. In practice, Northern interests prevailed over Southern grievances and autonomy for the South did not take place.

2.7 Security – No Guarantee for the South

The most contentious issue in the negotiations was the question of security for the Southern region, “[s]ecurity was where the fight for effective power centred during the peace talks”.157 The merging of the Anyanya and Sudanese government soldiers was not successful. One of the major factors leading to the resumption of fighting later in 1983 was the failure to demobilise and reintegrate the Anyanya forces effectively.158

“Most southerners assumed that integration of the two armed forces would take place after a period of five years, that the proportions of northern and Southern soldiers in the Southern command would remain equal, and that Southern troops would remain garrisoned in the South. The army insisted that the absorption process would be complete within five years but there were no clear provisions in the Agreement for the status of the army after that period”.159 Following the five-year transition period many in the region were dissatisfied. The full quota of Anyanya (6,000) had been absorbed but the northern troops in the south were not reduced. Many senior Anyanya were either retired early, purged, or transferred out of the south.160 Nimeiri wanted to neutralise the power of Southern soldiers by transferring them to the North.

Distrust was – as it always had been, inherent and hindered the integration process. There were many guerrillas who remained in the bush who were unwilling to comply with the security provisions in the Addis Ababa Agreement.161 Divisions between North and South had become entrenched in the years following independence and conflict had torn apart cohesion amongst Southerners with differing ambitions regarding unity and separation from the north. Some Anyanya fighters refused to be integrated and were exiled, principally to Ethiopia and became key in the resurgence of guerrilla activity in the 1980s.162 By 1972, “a modus operandi had been established: Southern politics had been militarised”.163

Rising military resistance among former Anyanya forces occurred throughout the 1970s with mutinies taking place in Akobo in 1975, Wau in 1976 and Juba in 1977. Those mutineers – neither captured nor killed, escaped into the bush and found their way to Ethiopia. This led to the creation of the Anyanya II movement.164 Again, this was a loose organisation that was broadly separatist in its aims who linked up with other armed and disaffected groups in the country. They also attracted deserters from the army and the police,165 as well as “opportunistic bandits”.166

2.8 Oil Discovery

Confirmation of the discovery of large oil deposits within the north-south borderlands of Upper Nile and Kordofan was made in 1979. This followed the signing of the Addis Ababa Agreement and after the regional government had been established. The regional government was not consulted on the concessions granted to the companies, Total and Chevron, which served to deepen mistrust. Most of Sudan’s known oil deposits are in Upper Nile and Jonglei Provinces. As to the capacity, “[a]t one time, Chevron, who did the initial surveys, estimated the Sudan’s total oil reserves at 10 billion barrels”.167 Hassan al-Turabi, then Attorney General, subsequently attempted to redraw the southern region’s borders to include the oil fields of Kordofan. This underscored Northern dominance and that the oil fields would be placed under central, rather than regional control.

Nimeiri constantly interfered in the politics of the southern region and supported the idea of redividing the south into its original three provinces [Equatoria, Bahr el-Ghazal and Upper Nile]. Joseph Lagu first proposed this idea as he was resentful of the influence of the leaders of the Upper Nile and Bahr el-Ghazal in the Regional Government. Lagu did not receive Southern backing for this, but Nimeiri overrode this opposition in 1983 while unilaterally abrogating the Addis Ababa Agreement and thus dividing the South into three weaker regions.168 Nimeiri issued “Republican Order Number One” in June 1983, which called for the redivision of the south into three regions – Equatoria, Bahr el-Ghazal and Upper Nile, and enabled the central government to deal with each region separately, using tribalism to foment intertribal fighting.169 Alongside Nimeiri’s actions and disappointment in the peace process, plus conflicting agendas across the rebel factions, further civil war was inevitable.

The oil fields lay in predominantly Nuer territory. The Anyanya II factions would go on to lead the attack against Chevron’s operations as they saw the company as allied with the north despite Chevron’s efforts to stay neutral. The Anyanya II rebels stated they had targeted Chevron as a symbol of US cooperation with the Sudanese government, claiming that company survey planes were feeding Khartoum with intelligence – an allegation Chevron categorically denied.170

The continued fighting prevented development of the oil sector and therefore revenue from oil halted. Nimeiri negotiated with Anyanya II leaders from the Bentiu area to sign a separate agreement to pacify ‘Nuerland’ to enable Chevron to resume work which would mean that Nimeiri would get the money required to stay in power and consolidate divisions across the South.

2.9 Second Civil War: 1983-2005

In 1983, Nimeiri’s policies of re-dividing the south and imposing Islamic law served to erode southern sovereignty and increase community division and factionalism. The North had a deliberate policy of sponsoring various southern armed factions against the SPLA to drive the ‘ethnic’ dimension of the war. The government’s strategy of supplying tribal militias gave the war the trappings of a tribal conflict with little relation to national policies and, by fighting proxy wars in the South, the government could claim – with little opposing evidence, that it was not fighting a civil war.171 Khartoum’s divide-and-rule tactics created rivalries and competition for resources in the South.

The SPLM/A was founded in 1983 out of an amalgamation of Anyanya II and mutineers based in Ethiopia. From the outset, there were divisions within the SPLM/A over its leadership and the group’s aims. Some wanted to pursue calls for independence and others called for a “New Sudan” to be created encompassing equal powers for the whole of Sudan and separation between religion and the state. The SPLA learned from the localism and factionalism of the Anyanya and deliberately set out to create a unified force.

The formation of Sudanese People’s Liberation Army in Ethiopia, made up of some Anyanya II fighters and other Southern rebel units, was led by John Garang, a Twic-Dinka by descent. Garang was leader and head of the political wing, the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement. Garang’s support for a New Sudan ran at odds with the Southern autonomy expressed at independence by the Anyanya.

2.9.1 Disunity, Arms and Militias

Full unity of Southern forces did not exist in the SPLM/A, as dissatisfaction and resentments ran deep. The GoS provision of arms and funds to other rebel groups, was also a cheap way of attacking the SPLA without committing their own forces. This approach continued to be a major factor in the conflicts of the 1980s. Khartoum’s support for these groups, however, did not mean loyalty to the North. Many of the militias were composed of the rural populace and used the war to pursue their own objectives. Some militia members went to war to settle enmities with neighbouring ethnic groups under the guise of a religious war.172

In 1984, Nimeiri exploited the infighting between the Anyanya II and the SPLA, as well as ethnic divisions between the Nuer and the Dinka, which were argued to represent the Anyanya II and the SPLA respectively.173 Some Anyanya II rebels joined the SPLA and others contacted Khartoum for arms, ammunition and uniforms to form a pro-government Southern militia.174 Nimeiri was able to use these divisions to his economic advantage in order to achieve his own political agenda.

2.9.2 Anyanya II: Nuer

The Anyanya II were predominantly from the Nuer, the second largest ethnic group in the south and fought in rural areas with the support of the government of Sudan. Groups of Anyanya II were recruited from quite specific sections: from the Gaajak Nuer of Maiwat, the Mor Lou Nuer of Akobo, the Lak and Thaing Nuer of Zeraf Valley, and the Bul Nuer of Western Nuer. Presented by foreign observers as a Nuer-Dinka split, in fact most Anyanya II – SPLA fighting took place with groups of Nuer on both sides. Military successes for the SPLA in 1987, eventually saw most Anyanya II fighters defecting to the SPLA and by mid 1989 only one Anyanya II faction remained loyal to the GoS.175 In 1987-90, the SPLA achieved a rapprochement with the majority of Anyanya II units, using mainly Nuer commanders and politicians as intermediaries.176

2.9.3 Omar al-Bashir

The SPLA fought against the GoS until 1989, when the parties reached a peace agreement that suspended sharia law in the South. However, on 30 June 1989, a military coup led by Brigadier Omar al-Bashir overthrew the Sudanese government and repudiated the peace agreement. Omar al-Bashir remained in power for almost thirty years, until he was removed by security forces who withdrew their support for his regime after months of protests in 2019. His longevity in office has been attributed to the fact that powerful rivals in the ruling National Congress Party distrusted each other more than they did al-Bashir.177 His rule was defined by war and his desire to keep Sudan unified came to an end with the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005, which laid the foundation for independence of the south in 2011.

Dr. John Garang addressing the National Congress Party

2.10 SPLM/A

The SPLM/A has been described as progressing from a Marxist group supported by Ethiopian backers, to a dis-united faction-prone organisation, to a group with its own constitution and self-proclaimed democratic system of governance.178

The SPLA leadership learned the lessons of the first war extremely well and made the control of internal factions one of their initial political objectives. Their political cohesion was one of the factors in their military successes.179 John Garang was clear from the outset that he was fighting for a unified Sudan, not its separation. This put him at odds with others who wanted separation. Yet, despite Garang’s authority, the SPLA and its disparate armed wings were spread across the country: command and control on the ground was dependent mainly on local commanders and these were not always aligned with the centre. The SPLA were successful in fighting against the north and in expanding their areas of control but the focus on the militarisation of the organisation posed political challenges.180

Garang tolerated no dissent. The SPLA had controlled internal dissent to avoid the internal ruptures that had fuelled the first civil war. CIA assessments praised Garang as an adept tactician but again forewarned of “internecine strife ahead”.181 Personal rivalries, identity politics and ideological differences ultimately destroyed cohesion from within. Each of the leaders believed their vision for the south was the better one. The divisions would lead to some of the worst fighting the south had ever seen. It divided the SPLA along bitter ethnic lines.182

2.11 SPLA Internal Coup of 1991 and Factionalism

In 1991, the Derg government in Ethiopia, led by Mengistu Haile Mariam, was overthrown and the SPLA lost one of its main sources of support and arms. The new government expelled SPLA forces.

The internal SPLA coup of 1991 (so called Nasir Declaration) represents the foremost divisive and damaging split to the movement. Three senior SPLA commanders, Lam Akol in Upper Nile and Riek Machar in Nasir along the Ethiopian border, along with Gordon Kong, called for the replacement of John Garang as leader. They accused Garang of aligning himself too closely to Ethiopia and independence was therefore forestalled. The rebel movement split into two factions: the SPLA-Torit or Mainstream, commanded by John Garang, and the breakaway SPLA-Nasir, or United, commanded by Riek Machar. Their political ambitions were divided: Garang was fighting for a united Sudan and the SPLA-United were fighting for independence.

The conflicts following the 1991 split were “qualitatively different from that of conflict that had gone before”.183 Previous conflicts had been shorter, subject to local ethical codes and receptive to reconciliation rituals being carried out. The post-1991 violence was more brutal and indiscriminate, “[e]veryone recognised that this violence had little to do with the daring, cross-border, cattle raids staged by generations of Nuer and Dinka youths seeking to demonstrate their courage and fighting prowess”.184 The conflict and the militarisation of society that accompanied it had long and profound consequences for structures of authority and peace-making, resulting in the conflicts becoming protracted and entrenched. The legacy of this break-away continues to weigh heavily on South Sudan today.

The motives and outcomes of the Nasir Declaration were murky. Tribal animosities came to the fore during discussions and affected the outcome. The split enabled Khartoum to direct and regain military dominance in the South.185 Following the reconciliation of the Anyanya II with the SPLA in 1987-90, many Anyanya troops were not incorporated into the SPLA but remained in their home areas. During the 1991 split, Anyanya II troops sided with the Nasir faction under Machar, attacking civilians in Bor and Kongor district, repeating tactics they had used under Khartoum’s direction.186

In 1993, the SPLA-Nasir became the SPLA-United when it merged with other militia groups in the south. The factional fighting spread during 1992 and 1993 from Jonglei to Western Upper Nile (today’s Unity State), Bahr el-Ghazal and eastern Equatoria. Some militias were allied to the GoS throughout the war, as were Paulino Matip’s forces in Unity. After Kerubino Kwanyin Bol – a veteran of Anyanya, officer in the Sudanese army and a founder of the SPLM/A, was freed from prison by forces loyal to Riek Machar and Lam Akol, Warrap and western Bahr el-Ghazal were overwhelmed by factional fighting.187

In 1994, following a Nuer reconciliation meeting, SPLA-Nasir adopted the title the South Sudan Independence Movement/Army. The Nasir movement failed to create a cohesion, with many Nuer commanders and soldiers returning to the SPLA.

Factionalism continued amongst the SSIM and the tensions between Paulino Matip and Riek Machar intensified. Most of Machar’s commanders had defected ahead of him to join Khartoum’s forces. Mercurial warlord, Peter Gatdet, a Bul Nuer from Mayom County who had been armed and fought for the SPLA in the 1990s, joined forces with Machar in support of Khartoum in the late 1990s and then went on to lead a mutiny against Paulino Matip’s pro-government militia in September 1999. Most of Paulino’s Bul Nuer soldiers mutinied with Gatdet, which left Paulino with a shell of a militia. Kerubino Kwanyin Bol, who had also defected to the GoS, died during Gatdet’s mutiny in Mankien.

Following reconciliation in 1994, in 1996 Riek Machar went on to sign a peace charter with Khartoum, that allied him and his forces to the north and against the SPLA and then he followed this by signing the Khartoum Peace Agreement in 1997. The SSIM became the South Sudan Defence Forces, an army formed under the KPA.188 For the GoS, it did not matter that they were supporting a secessionist-based movement, as what was important to them was the support for a group fighting against the SPLA and ultimately its demise. The Sudanese government focused on destabilisation in the south to sow discord amongst the different factions. The changing allegiances of the SSDF demonstrated that destroying rivals was more important than promoting ideology. Various southern armed factions enjoyed Khartoum’s patronage until 2000 when Machar left government in Khartoum and took up arms against the North, forming the Sudan People’s Democratic Front. Then, in 2002, Machar signed a peace agreement with John Garang merging the SPLA with the SPDF militia to conduct military operations against the GoS.189

2.12 External Involvement in the Wars of the South

During the 1980s, US military sales to Sudan continued against the backdrop of the Cold War. The Reagan administration was fearful of both an insurgency and another anti-American government in power in north Africa. It was therefore prepared, to a certain extent, to ensure a friendly government remained in power. Nimeiri was able to exploit Libyan aggression and Ethiopia’s Marxist regime’s relations with the SPLA to ensure cooperation with the Americans. This support waned however as USA and USSR relations thawed and Sudanese government economic failures continued.

The Cold War saw a shift in alliances as Sudan pivoted against an international structure split between USA and USSR sympathies. However, allegiances were never predetermined. Nimeiri initially courted the Eastern Bloc with his socialist goals but the attempted coups by the Communists in 1971 saw a break with the USSR. Diplomatic relations were resumed with the USA in 1972, which saw a period of strengthening relations with the West.

This created a rift with Qaddafi’s Libya but the economic and military assistance from America offset this divide.190 Chevron’s increasing involvement in Sudan saw stronger US interest with financial assistance for development projects, infrastructure and servicing of the national debt.

The overthrow of Haile Selassie in 1974, a subsequent alliance between Ethiopia and the Soviet Union and the election of Reagan in the US in 1980, all combined to influence Sudan’s role in international politics.191

Israel trained Anyanya recruits and shipped weapons via Ethiopia and Uganda to the rebels. Qaddafi bankrolled the SPLM/A initially as the proxy wars and politics of other countries were laid bare through the conflicts of north and south. Qaddafi’s issues with Nimeiri led to greater regional tensions and the guaranteed funding of rebel forces.192

Sudan’s relations with the West changed in the 1990s following the collapse of the Soviet Union. American political relations firmly shifted following Khartoum’s support for a more militant Islam and for Saddam Hussein in the First Gulf War. The SPLA now fought against a government that openly hated the USA. In return, the USA now viewed the southern Sudanese rebel movement through a more receptive lens. The fear posed by the spread of extremist religious ideology and consequent security issues would ensure American support for the rebel movements in the South.

The SPLM seized this opportunity and spoke internationally about the hope of peace, development, and equality; all bound in religious discourse to appeal to an influential American religious lobby. The language used described the suffering of an oppressed Southern Christian minority in misery and threat, against resurgent slavery from the Islamist North. These themes resonated in America and won them influential religious backers.193

The American religious lobby group became an ardent and vocal ally for the south Sudan SPLM cause, with “the conflict in Sudan remain[ing], ‘Africa’s forgotten war’ – until, that is, the American religious community engaged the cause”.194 John Garang was able to use his international platform to emphasise the Christian beliefs of many south Sudanese and highlighted efforts by Khartoum to impose sharia law upon the whole of Sudan. Against the backdrop of rising international tensions surrounding the rise of militant Islam, his words captured the attention of the Evangelical Americans.

The diplomatic support and development aid from the USA to the SPLM/A in the later 1990s/early 2000s, would eventually see the American’s become the “midwives” at the birth of an independent South Sudan. They helped facilitate the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005, which enabled eventual secession from Sudan in January 2011. Crucially, factionalism was not addressed during this period and rivalries between armed groups ran deep, alongside the proliferation of arms. The divisions across the many heavily armed groups in South Sudan, continue to hinder and impact the country’s peace and progress today.

Nuer community defence group known as the White Army

3.1 Introduction

The prevailing way of life in South Sudan is traditional agriculture involving the raising of livestock. For decades and longer, this way of life has led to acute competition and violent conflict over natural resources, such as water, fishing and grazing, among the various communities. Farmers and nomadic herdsmen in undeveloped rural areas have historically clashed for long-standing reasons, unconnected with politics. Cattle are an important index of wealth and cattle raiding has long been rife among the ethnic groups, accompanied by violence and the abduction of women and children. These clashes have become more violent and deadly as traditional weapons have been replaced with modern hardware including rocket-propelled grenades and machine guns.195 The state has had difficulty in controlling this violence while external actors have perpetuated a conflict narrative focusing on ethnicity rather than seeking to engage with the historical legacy of the country and the deep-seated grievances.196